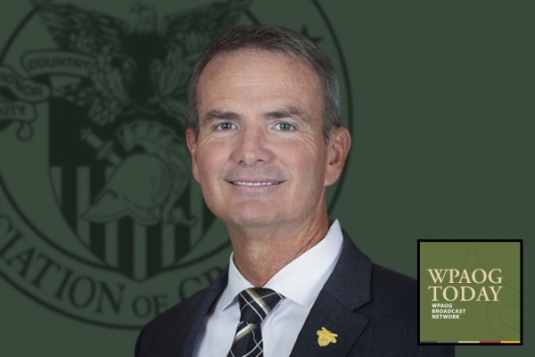

By Rebecca Rose, WPAOG Multimedia Journalist

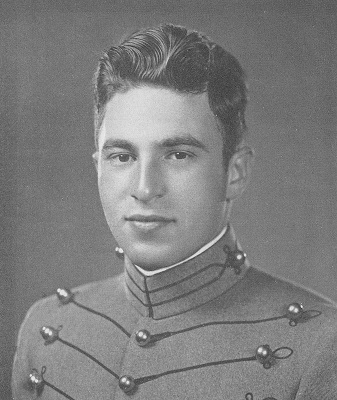

WPAOG would like to recognize COL (R) Herbert I. Stern ’41 as our Oldest Living West Point Graduate. Born on December 24, 1918, Stern will celebrate his 105th birthday this year. Stern knew he wanted to attend West Point by age 12, and after graduating from high school at 16, attended a one-year prep school. Stern received his appointment through the competitive exam from the Civil Service Commission after the Maryland Senator Radcliffe had promised him his appointment but then gave it to someone else. He reported to the Academy on July 1, 1937.

Cadet experience

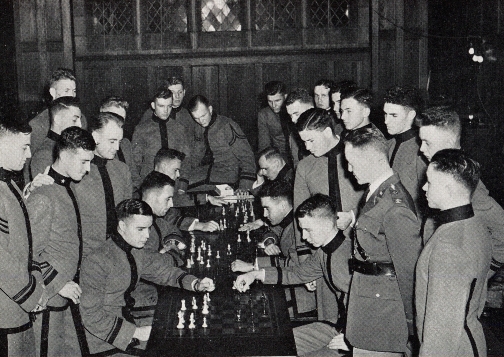

Known as “Herb,” he was known by his classmates for having “just the right mixture of adventurous, fun loving spirit, a calculating, ambitious mind, and a deep understanding heart to make an excellent soldier and a grand pal.” He played on the soccer team, was a member of the fishing, camera and chess club and graduated as a Cadet Sergeant.

During his time at the Academy, cadets were required to take four years of equitation (horse riding). “In those days, the Army still loved horses, and in each of my four years at West Point, I underwent cavalry training,” said Stern, who admitted he hated horses, and “they hated me.” Prior to graduation, Stern had selected to branch Field Artillery but ultimately changed his mind after the chief of Field Artillery came to West Point and told them he was going to do all that he could to ensure they were assigned to horse units. He then opted to enter flight training following graduation.

Early career

He went through primary training in Tulsa, Oklahoma and went to Randolph Air Force Base in Texas for basic training. Stern had soloed already when he and some friends got caught pitching pennies by their instructor who delayed their training. Stern was going to be held back one class for being behind in his training and decided to return to field artillery. When the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor made its way to Stern, he was shooting pool in the officer’s club at Randolph Field. After the attacks, Stern and other soldiers loaded onto trains they thought were headed to the Pacific, but they just went to Fort Sill, Oklahoma for a short time.

There, Stern ultimately ended up with the 84th Infantry Division under BG Ivan Foster. Stern joined the unit as the Headquarters Battery commander. Foster felt he needed to be in a firing battery and transferred him to the 327th Field Artillery as the Battery B commander. In January 1942, he reported to Fort Jackson, South Carolina and the 8th Infantry Division Artillery. After three days there he was sent to Fort Sill to take the basic field artillery course. He spent three months there and met his future wife, Rose Horner, who was a student at the University of Oklahoma. He then reported back to Fort Jackson and was assigned to Headquarters Battery, 8th Division Artillery.

For his first duty assignment, Stern reported to then CPT Wohlfeil ’39, who informed Stern that he was now the commander of the battery. Stern said he felt lost and he had to learn how to command from his non-commissioned officers. During this time, he and his wife Rose were married. Later, GEN John Hildring asked Stern to join his new division, the 84th Infantry Division in Camp Howze, Texas, after inspecting the entire 8th Division and finding that Stern’s Headquarters Battery was the only unit doing serious training. Before his first combat engagement, Stern went to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana on the way overseas. While there, he learned of a moving target artillery range at Camp Polk and asked to take his battery there for training in direct targeting, but his battalion commander said no. Stern insisted and the commander eventually relented. Months later, that training would save their lives.

World War II

When the Battle of the Bulge began on December 16, 1944, Stern’s unit was with the northernmost American division and so they were moved to the Bulge. They arrived in Marche, Belgium on December 19. In the Bulge, the battalion commander spent most of his time with the regimental infantry commander. Their main job was to directly support the 333rd Infantry Regiment. Stern was left with the battalion, since he was the senior major. The first night in Belgium, Stern walked down a road and a Belgian woman was walking up the road waving her hands and screaming, “Les Boches! Les Boches!” meaning “Germans!” In all of the chaos, Stern had no idea if anyone was in front of his artilleryman, and normally artillery move behind the infantry. Stern moved the battalion behind an infantry unit he had been able to locate. That night, the Germans took over the area they had just left. For artillery to fire accurately, the unit must register the guns, and the forward observers could not see anything at all due to the fog and snow. Stern decided to defy orders not to leave the command post and observe for himself, where he found a crossroads he could identify. That night, an armored German force came through on that crossroads and 12 American battalions were able to fire upon that force, which Stern feels stopped the German penetration there.

In Belgium, before arriving in the Ardennes, Stern and his men were shown the brand-new variable time (VT) fuze, a fuze that would burst about 20 yards above the ground. They trained on the VT fuze near Aachen, Germany. During the Battle of the Bulge, they used them with devastating results for the enemy. The resulting shrapnel field would be deadly for Germans in foxholes or under cover and they used those fuzes for the rest of the war.

Stern and his unit left the Bulge and returned to northern Germany. They crossed the Roer River and went through the Siegfried Line moving to the Rhine River. They were in combat this entire time. While in northern Germany, Stern officially took command of his battalion when his commander left to replace the division artillery operations officer. GEN Charles Barrett visited and told Stern he was not the senior major in division artillery, but Stern told Barrett that until they sent someone senior to them, he felt he was the commander, which Barrett reluctantly accepted . About three days later, one of the infantry regiments was placed in Corps Reserves, freeing up an artillery battalion. A group was formed of two battalions to support the 333rd Infantry Regiment. This meant Stern was now the commander of two battalions, the 909th and 325th Field Artillery Battalions.

While moving his battalions, they were attacked by a German tank unit. Thankfully, Stern and his unit had completed the direct targeting training back in Camp Polk, Louisiana. The 325th battalion engaged the tanks directly. Stern called for infantry support and LTG Alexander Russell Bolling sent them a force. The Germans moved into a wooded area, but were out of high-explosive ammunition. The Germans managed to destroy all of the American service equipment and U.S. trucks on fire all of the unit’s mail was lost, and three men were captured, but ultimately there was no loss of life. The 325th battalion was recommended for a Presidential Unit Citation by LTG Bolling, but was turned down both times because there were not enough casualties. (Stern feels that is the reason they should have gotten the award.)

After the war

Later, while Stern was driving through Salzwedel, Germany and discovered a concentration camp with 3,000 Jewish women being held captive. Stern and his men opened the gates, released the women, and burned the camp down. Later when his unit was stalled waiting for the Russian Army, Stern went back to see what had happened to the women. Since they had received care and food, Stern said he could barely recognize these same women; they were like different people. After a few other assignments including a year at the French War College in Paris, Stern returned to the U.S. in 1947.

Upon his return he was assigned to Headquarters, Army Ground Forces at Fort Monroe, Virginia for three years. After working on the Department of Defense Standardization Committee, Stern was ordered to Saigon, Vietnam in 1950, because he had attended the French War College and the French were in command there at the time.

Following a three-year assignment with the Department of the Army general staff in logistics, Stern spent one year at the Army War College before being assigned to NATO headquarters in Naples, Italy. He was involved in the defense planning for the eastern NATO area of Turkey. While in Italy, Stern’s son Robert was born.

Later career

Stern’s next assignment was to the Joint Advanced Study Group in the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. When GEN Dwight D. Eisenhower, West Point Class of 1915, was Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, he had created a group of young officers to look 20 years into the future. The Joint Chiefs took that concept to the Joint Staff. Stern represented the U.S. Army in a group of four who spent two years doing this work. Stern was extended for one more year and worked directly for President Eisenhower. Eisenhower had a highly classified problem he wanted the answer to. Stern and his group spent a year working on the top secret problem. The group gave their final presentation to the President in the White House with no one present except for the President’s son and GEN Andrew Goodpaster ’39, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander in Europe from 1969 to 1974. After the presentation, the Eisenhower told GEN Nathan Twining, Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force from 1953 to 1957, that the study group could make the presentation to the Chairmen of the Joint Services, but that they were not allowed to comment. Stern and one other study group partner made the presentation. Stern then left the Joint Chiefs of Staff assignment and because of the research he had worked on, was prohibited from leaving the United States for two years.

After a few other assignments, Stern was assigned to the Combined Military Planning Staff of the Central Treaty Organization headquartered in Ankara, Turkey, which took him to Iran as well as Turkey. He spent two years there. While in Tehran, Iran, GEN Earle Gilmore Wheeler, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1964 to 1970, was having a reception where he told Stern he wanted him back on the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Stern told Wheeler would only return if he received a promotion, which Wheeler could not do. In Washington D.C., a friend told Stern there were orders for him to return, but Stern refused. Stern was placed on an emergency reserve list for the Joint Staff and then sent to the Institute of Advanced Studies at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. There, he was the chief of the strategy branch. After two years he decided to retire.

Stern was married to Rose Horner and they had one son together. Rose died in 2015 after over 70 years of marriage. Last year, Stern was interviewed on the CBS Evening News in honor of Veteran’s Day. He is the last living member of the West Point Class of 1941 and stated, “I miss a lot of my classmates. We were a very close class since we graduated right into the war.”