By Keith J. Hamel, WPAOG staff

While West Point’s internal values are permanent and timeless, its external face and footprint are perpetually changing. One way to mark the physical changes at West Point is to look at where its famous structures, namely its monuments, used to be located versus where they reside today, as well as to examine how some of these monuments have been altered over time.

Wood’s Monument (1816)

Named in honor of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Eleazer Derby Wood, Class of 1806, who was killed at the Siege of Fort Erie during the War of 1812, Wood’s Monument was erected at West Point in 1816, making it the oldest monument at the Academy. According to Colonel George S. Pappas ’44 (Retired), the late founder of the U.S. Army Military History Research Collection (now known as the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center), Wood’s Monument originally stood in front of South Barracks, at the approximate site of Eisenhower Barracks today. Sylvanus Thayer, Class of 1808, had the monument moved to a knoll on the southwest corner of Trophy Point, where it was placed next to West Point’s flagpole. Reports suggest that Wood’s Monument was used as a navigational aid for ships on the Hudson River, and the 15-foot-high, four-sided obelisk was prominently positioned for visitors ascending to the level of the Plain via a dirt road that led up from the post’s dock. During his first tour as Superintendent (likely when the Ordnance Compound was being built [1838-40]), Richard Delafield, Class of 1818, wanted to move the monument to the West Point Cemetery and level the mound upon which it stood, but graduates strongly objected to this. In 1885, however, with the Academy expanding, Delafield’s plan was put into effect. Wood’s Monument was moved to the cemetery, where it is currently near the graves of Susan and Anna Warner.

Kosciuszko Monument (1828) (1913)

Originally merely a base and fluted column, the Kosciuszko Monument was dedicated on July 4, 1828. It was designed by John H.B. Latrobe, an ex-cadet from the Class of 1822, and paid for by cadets, who volunteered 25 cents each from their monthly allotment. The eight-and-a-half-foot bronze statue of Tadeusz Kosciuszko, the Polish officer and engineer who assisted the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, was mounted on top of the column 85 years later, upon the initiative of Polish American clergy and laity who raised the necessary funds. Since then, local Polish American communities of New York have been holding regular observances at the monument. In 2021, during an annual inspection of all West Point monuments, the column and base of Kosciuszko’s Monument was found to have developed structural cracks. Accordingly, the statue and column were removed and placed in storage until the base can be repaired. The monument is appropriately located on the site where Fort Clinton, the Revolutionary War fortification designed by Kosciuszko, once stood.

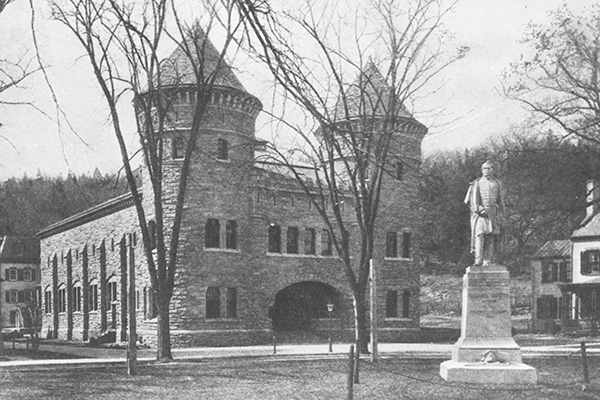

Dade Monument (1845)

According to Pappas, “Dade’s Monument should have been mounted on a wheeled pedestal.” It was erected in 1845 to commemorate Francis L. Dade and 108 troopers under his command (including four graduates: George Gardiner, 1814; William Basinger, 1830; Robert Mudge, 1833; and John Keais, 1835), who were killed on December 28, 1835 while attempting to force Seminoles off their land in Florida. The monument originally overlooked the Hudson River, located on a grassy hill surrounded by trees near where Cullum Hall stands today. It was then placed across the road from Cullum Hall in 1898. In 1917, it was moved to the front of the Old Cadet Library. Finding that it interfered with baseball games on nearby Doubleday Field, the Academy had the Dade Monument moved in 1950 to its current home near the entrance to the West Point Cemetery.

Sedgwick Monument (1868)

Sedgwick Monument was erected by officers and soldiers of the VI Army Corps to commemorate their commander, Major General John Sedgwick, Class of 1837, who was killed during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in 1864. Dedicated in 1868, the statue is rumored to be cast from a Confederate cannon captured by VI Corps. The Sedgwick Monument was originally located on the northwest edge of the Plain, which made it easier for academically deficient cadets (in full dress, under arms) to reach it and spin the statue’s moveable spurs, fulfilling the lore that doing so would help them pass a term end exam. However, around 1970, when the Thayer Monument was moved to the northwest edge of the Plain to make room for Washington’s Statue in front of the Mess Hall, the Sedgewick Monument was moved east along Washington Road and placed just south of (and across the street from) Battle Monument.

Custer Monument (1879)

The original Custer Monument was designed rather similarly to the Sedgwick Monument: a life-sized bronze statue atop a granite pedestal. It originally stood across from the old Cadet Mess (on what would be the site of today’s Bartlett Hall), with Custer, the last man in his June 1861 Class, defiantly facing the river and not the Academy, perhaps the least in a series of controversies surrounding the monument. Even before the statue was erected in August 1879, the surviving spouse of the commander of the 7th Cavalry at the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn objected to the way her husband was depicted. The sculptor, James Wilson MacDonald, relied on inaccurate drawings of Custer made by William Cary, causing him to make several troubling design choices: the uniform he was wearing, the weapons he was holding (and their position), and the expression on his face. Petitioning the highest authorities, Mrs. Custer succeeded in her efforts to get the Academy to remove the statue. In 1885, the base of the Custer Monument was moved to his grave in the West Point Cemetery, and Mrs. Custer had a stone obelisk added to the base in 1905. But what happened to the statue of Custer? In 1898, West Point’s Quartermaster consulted Mrs. Custer about removing the statue’s head and mounting it for display, to which she agreed. Two years later, Stanford White, the architect for Cullum Hall, was asked to supervise the project. He discreetly moved the statue to New York City but was murdered on June 25, 1906, and the secret of the final disposition of Custer’s statue died with him.

Thayer Monument (1883)

Thayer Monument was unveiled on June 11, 1883. After a dedication speech in the Old Cadet Chapel by George Washington Cullum, Class of 1833, who funded much of the monument’s cost, a ceremonial party, led by the West Point Band, marched to the southwest corner of the Plain, near what is now Washington Hall, where the Thayer Monument was draped in flags. After a 10-gun salute, the monument was unveiled. Photos from the Academy’s centennial show the monument in front of the Old Gymnasium, which was built in 1891 just to the west of the Cadet Barracks (later known as Central Barracks). When the Corps expanded in the mid-1960s, Thayer Monument was moved to a small rise near Trophy Point. It’s position there was only temporary, however, as Academy leadership decided that the monument should be on the parade ground, nearer to the cadet area (and to the Superintendent’s Quarters). Thayer Monument was moved to the northwest corner of the Plain, its current home, after June Week 1973. This prominent site makes the monument visible to both cadets and visitors, and it is convenient for alumni ceremonies honoring “Colonel Thayer, Father of the Military Academy.”

Washington Monument (1916)

A replica of a bronze monument that was sculpted by Henry Kirke Bowne and erected in New York City’s Union Square in 1856, West Point’s Washington Monument was obtained by an anonymous “patriotic citizen” and unveiled at the Academy on May 19, 1916 (according to that year’s Annual Report of the Superintendent). Memorializing the commander of the Continental Army and the first President of the United States, Washington Monument first resided at the intersection of Washington and Cullum roads in front of Trophy Point, on the north end of the Plain. In the early 1970s, Washington Monument was moved to its current location at the entrance to the Mess Hall. Interestingly, a 1966 “Monuments Study” by O’Connor & Kilham, the architects who changed the traffic pattern around the Plain, recommended moving Washington Monument to the former West Point Hotel site, calling it “the most important site on the Main Post.” While the realignment of the road between Trophy Point and the Plain is the literal reason for its repositioning, the symbolic rationale—placing the statue in front of the building bearing Washington’s name and having the advocate for the founding of the U.S. Military Academy face the Plain to watch over the cadets as they march on the famous parade ground Revolutionary soldiers once trod—gives more credence to its prominent position.

L’Ecole Polytechnique (aka “French”) Monument (1919)

Presented to the Academy in 1919 by the cadets of the French School, L’Ecole Polytechnique Monument is a full-size replica of a statue at France’s military academy that commemorates the cadets of that French school who died in defense of their country in 1814. It first stood along Old Diagonal Walk, on the south edge of the Plain right across the street from the central sally port of Old Central Barracks. With its golf-leaf finish gleaming in the sun, cadets nicknamed the monument “Gold Tooth”; however, Navy midshipmen doused the statue in blue paint prior to an Army-Navy Game in the 1940s, and the monument’s gold plating wore off when West Point removed the paint. When the Corps expanded in the mid-1960s, the Old Central Barracks were demolished, and the new construction forced Diagonal Walk to cut into the Plain. As a result, the French Monument was moved to its present location, inside Central Area next to the original 1st Division, where its sculpting mistakes—cannon balls too large for the cannon, straight scabbard yet curved saber, unbuttoned coat, and wind blowing the tails of the cadet’s uniform backward while the flag is blowing forward—can only be seen by members of the Corps.

Patton Monument (1950)

The Patton Monument was dedicated by the famous World War II general’s surviving spouse, Beatrice, in 1950. It was originally located east of Thayer Road opposite the Old Library. In fact, Patton’s statue faced the library. It is rumored that the decision was made to have the statue for George S. Patton Jr. be facing the library because he was turned back to the Class of 1909 for being academically deficient. Therefore, his statue, sculpted with binoculars in his hands, was deliberately placed so that “he” could always locate the library. In 2004, when construction began on Jefferson Hall, the new USMA Library, the Patton Monument was placed into storage. On May 15, 2009, approximately one month to the centennial of Patton’s graduation day, his monument was placed in a new location on the northwest corner of Jefferson Hall. This location was only meant to be temporary. The monument’s permanent location was supposed to be near the right field foul pole of Doubleday Field, facing northwest towards the Plain, but for the last 14 years and counting Patton hasn’t been able to escape the pull of the library.

Buffalo Soldier Rock (1973) (2021)

In 1973, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point became the first institution to memorialize the achievements of Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiments, who once taught horsemanship to cadets (1907-47). The Cavalry Plain on the south side of post was renamed Buffalo Soldier Field and a memorial rock was placed in the northeast corner of that field. Decades later, members of the Buffalo Soldiers Association of West Point began working to transform Buffalo Soldier Field’s “Memorial Rock” into a more visible monument. At the 57th annual Buffalo Soldier Memorial Ceremony, Major General Fred Gorden ’62, West Point’s 61st Commandant, remarked, “What we would like to do is transfer the rock, because…this rock is insufficient and not a fitting representation of the Buffalo Soldiers—we need a statue.” A monument featuring a Black trooper mounted on horseback was unveiled on the west side of Buffalo Soldier Field in September 2021, with the plaque from the original rock mounted on the base of the new statue.