A distinguished journalist and author who has fulfilled the roles of editor, domestic and international news reporter, war correspondent, television anchorman, host of television news specials, and historian, Thomas J. Brokaw has devoted a lifetime of service to his profession and in so doing, has profoundly benefited the Nation. In a professional career of more than forty years, he has kept the American people informed with steadfast devotion to the highest ideals of his calling and has thus proved himself an exemplar of West Point’s motto, “Duty, Honor, Country. “

Of particular note are his chapters in the great narrative of our Military’s valor and sacrifice. His two books on the “Greatest Generation, ” his reporting from Afghanistan on the hunt for Al Qaeda, and his broadcasts from Iraq on the superb performance of American soldiers have contributed significantly to our country’s high respect for its Armed Forces, both past and present, a respect that Tom Brokaw himself shares.

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson spoke thus on the importance of a free press:

The basis of our government being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.

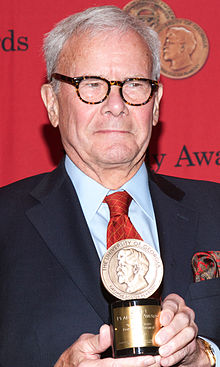

More than 200 years later, freedom of the press retains its central importance to the vitality of American democracy, and Tom Brokaw has earned a place in the first rank of those who have wisely exercised, bolstered, and preserved that freedom. Accordingly, the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy takes great pleasure in presenting the 2006 West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award to Thomas J. Brokaw.

Article

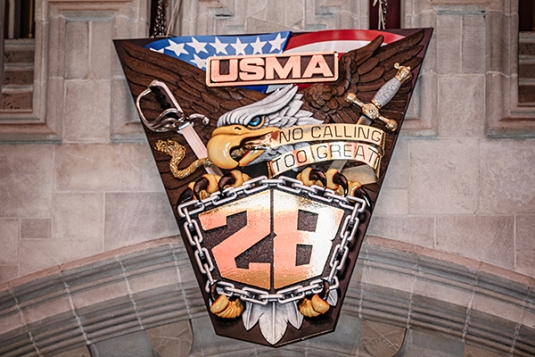

It was one of those beautiful, pre-autumn afternoons at West Point: sunny, temperature in the seventies, and some slight changing of color in the leaves of the trees along the Hudson River. In just over 24 hours, autumn officially would arrive. At 3:15 on the afternoon of 21 September 2006, however, guests began arriving at the West Point Club for the reception in honor of this year’s West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award recipient, retired journalist and TV anchorman, Tom Brokaw, and his wife. The crowd was larger than usual to meet and greet only the second journalist to receive the Thayer medal, Walter Cronkite having been the first in 1997. Brokaw is a rather big man, a “flanker,” and he stood at least a head taller than most of those milling about him at the reception. Then he was spirited away to a news conference in an upstairs room of the club, where he observed that relations between the military and the media, strained during and after the Viet Nam War, were improving considerably.

After the crowd of guests moved to the Plain, the Corps of Cadets conducted a full brigade review, and Brokaw, accompanied by the Superintendent and the Cadet First Captain, inspected the assembled Corps by jeep. After posing for countless photographs upon the completion of the ceremony, the honoree was then spirited away to Quarters 100 while the Corps and guests assembled in Washington Hall for dinner. This was LTG Hagenbeck’s first Thayer Award ceremony as Superintendent, and he did the honors of introducing the recipient, citing his many accomplishments reporting both domestic politics and international events.

Brokaw began his remarks with some well-received jibes at Navy and Air Force. He said that he had to remember that he was at West Point, not at Annapolis, since if he were speaking to the middies he would have to speak slowly and use smaller words. For the Air Force Academy, he would have to be out of shape. Then he introduced a member of The Greatest Generation who was a guest of honor at the day’s events, attorney Leonard Lomell. As a member of the 2nd Ranger battalion, “Rudder’s Rangers,” and acting platoon leader, Lomell climbed the Pointe du Hoc on D-Day, even though wounded, and then moved inland to find and destroy the artillery pieces that were not in their expected location in the emplacements atop the Pointe. Ironically, the guns had been in their alternate location for a long time, untouched by the pre-invasion bombardment, and were aimed towards Utah Beach rather than Omaha Beach. Lomell was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Purple Heart.

As the author of The Greatest Generation and The Greatest Generation Speaks, Brokaw established one of his major themes: that the Americans who left their families and jobs to serve in World War II made great sacrifices, just as today’s cadets are doing. Thus, the Greatest Generation is, in some ways, part of today’s Long Gray Line, and today’s cadets are a continuation of that greatness. In a war against a misguided and tenacious enemy such as we face today, we cannot rely solely upon America’s volunteer military. All Americans must play a role. “In a way, we are all in the Army now.”

Then he voiced a second theme: the common bonds among soldiers and journalists. “Warriors and journalists come from the same gene pool. We both like to catch the bad guys.” Now that technology allows reporting in real time, reporters and the military must work together to inform the public without interfering with military operations. Common ground rules and a common understanding have to be established. “That almost always happens on the battlefield.” He then emphasized that “They’re boots-on-the-ground, hands-in-the-dirt, living-in-scary-places kind of people. That’s what motivates them. And they’re patriots.” He also noted that 78 journalists have died while covering the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Thomas John Brokaw was born in Webster, SD, on 6 February 1940, attended the University of Iowa for a year before transferring to University of South Dakota to study political science and work as a radio reporter. Upon graduation in 1962, he married Meredith Lynn Auld, a former Miss South Dakota. He began his television career in Sioux City, IA, eventually joining NBC News in 1966, reporting from California. In 1973, he became an NBC White House correspondent for three years and covered the Watergate Scandal. In 1976 he began hosting the NBC Today Show, moving to co-anchor, with Roger Mudd, of the NBC Nightly News in 1981. He became the show’s sole anchor in 1983, reporting from locations around the globe. On 1 December 2004, Brokaw retired.

Upon completion of his remarks, the Thayer medallion was presented to Brokaw by LTG (Ret.) Stroup, Chairman of the Association of Graduates, and LTG Hagenbeck. Immediately afterwards, the Cadet First Captain presented a cadet saber on behalf of the Corps of Cadets. Brokaw then returned to the microphone to offer one final exhortation: Beat Baylor! [And we did, 27-20.] The evening concluded with a final benediction, the singing of the Alma Mater by the Cadet Glee Club, and the departure of the official party. While the cadets returned to the barracks to study for their next day’s classes, the guests descended the steps of Washington Hall into a pleasantly chilly evening. Many stopped in small groups to catch up with classmates and old friends, enjoy the serenity of The Plain and the Hudson River in the distance, and comment upon the rapid progress of the construction of the new cadet library, Jefferson Hall. Its infrastructure, in places, now reached to the second-storey level. All in all, it was a good night, and a very good night to be at West Point.

Your humble servant,

J. Phoenix, Esquire

Speech

Remarks by Thomas J. Brokaw

Upon receiving the Sylvanus Thayer Award

West Point – September 21, 2006

Humility is not a virtue that is easily associated with someone in my line of work but I am truly humbled by this honor. All of my visits to the Academy have been occasions for a renewed sense of pride as a citizen and a deep, abiding appreciation for the young men and women who form this Long Gray Line, giving over their lives to the cadences of Duty, Honor, Country.

It was enough to know that I was simply welcome here but now to have my name associated with the founder of this historic and hallowed place, well, it is a hoo-hah moment I shall carry with me forever.

It is all the meaningful because I am in the company of my superiors—my family and friends who are here, especially those who preceded your time at the Academy. They have treated this civilian and journalist with patience, wisdom and, most of all, friendship.

In turn, I cherish their friendship and I treasure their counsel. I am also grateful that they have resisted pointing out that the only way I could get into West Point is with a car and driver.

This honor I accept in the name of other warriors and their families in another time. What I call The Greatest Generation, the men and women who came of age in the Great Depression when everyday life was about deprivation and common sacrifice. Just as the dark clouds of that struggle began to lift, this generation was called to battle at home and abroad in the greatest war ever fought.

They did not hesitate to go thousands of miles across the Atlantic and thousands of miles across the Pacific, to take to the high seas—and the skies above—to defeat the maniacal forces of facism and imperialism. They were bound to those they left behind by a common commitment and common effort—as men and women at home went without so those on the front lines would have what they needed.

New weapons and new strategies were produced on the run.

Farmers grew more and ate less; in town neighbors shared victory gardens—and rationed gasoline, meat and sugar; women put on overalls and picked up welding torches—and everyone felt the loss when the casualty reports came in.

It wasn’t a perfect time. Japanese-American citizens were sent to internment camps and black Americans were subjected to the worst kind of racism. And how did they respond? They fought their way onto the front lines and performed heroically, more than claiming their place in the greatness of their generation.

When they all came home it would have been easy for them to say, “I’ve done my share. I will now lay down my weapons and worry only about me.” Who would have blamed them?

They returned to their home states or took up residence in new ones and plunged into the public arena as school board members, governors, senators, representatives—and presidents.

They also—for the first time in the history of warfare—gave the countries they conquered a fresh start by rebuilding their economies and, in the case of Japan, giving the Japanese a constitution and democracy.

The Greatest Generation were in every sense of the phrase, men and women alike, in uniform and out, citizen-warriors.

In their own way, they were part of your Long Gray Line—and you, in your own way, are an extension of their greatness.

You will leave here the best-trained warriors mankind has known, but I trust you will not forego your sensibilities and your obligations as citizens.

I fervently hope that throughout your career you will find ways to stay connected to those not privileged to wear the uniform of their country—just as they must work much more diligently to stay connected to you and your families.

Too many of your fellow citizens are physically, emotionally, and even intellectually removed from the realities of life and death experienced by those of your generation who have volunteered to protect this nation in military uniform.

We are in a war against a tenacious and suicidal enemy, resourceful and full of a misguided rage in the name of their faith. It is complex, confusing, and controversial, very controversial.

It requires the full attention and personal commitment of all of us, in uniform and out. We must find new ways of dealing with the rage in the Islamic world—and we must find new ways of finding common ground at home.

This war cannot be won on the military battlefield alone. There is no state to summon to the peace table in Paris or onto the deck of the USS Missouri.

We’re all in the army now and this army has many faces.

And as you go from here to your first commission and your new responsibilities you’ll encounter the American press in all of its modern forms, men and women, print and electronic.

They don’t salute and they seldom say “Sir,” but they perform an essential role in a democracy during peace and war.

They will not always see the world exactly as you do, but it is my experience that you will learn from each other and that on the battlefield you will have a bond that may surprise you because—and this is sometimes hard for my friends in the military to accept—warriors and journalists come from the same gene pool.

They like to catch the bad guys. They live unconventional lives. When necessary they, too, can live off the land with their boots on the ground and spend their nights in scary places. They deal in facts—and, yet they, too, experience the fog of war in their own profession.

And they are patriots, stewards of a fundamental right of free people: a free press, however imperfect it may be on some occasions.

In this war, to a greater degree than any other in American history, warriors and journalists have another bond: death and wounds.

Bob Woodruff of ABC News, Kim Dozier of CBS, and Michael Weiskopf of TIME magazine were all grievously wounded attempting to tell your story. Weiskopf has eloquently described his perilous passage from writer to war casualty, his treatment at Walter Reed, and his insights into and admiration for his fellow ward mates. Michael’s book is tellingly called BLOOD BROTHERS.

More journalists working for American organizations have died in this war than in any other. Michael Kelly of The Atlantic and David Bloom of NBC News were lost in the early combat rounds. Since then 78—20 this year alone—journalists working for American organizations, most of them foreign nationals, have been killed or died in carrying out their duties.

In war and peace and in uniform and out, in our differences and in our similarities, we’re all privileged to be American citizens and to be stewards of the rule of law and democratic principles that remain the envy of the world.

Finally, let me offer a unique piece of military advice based on a little-noticed historic fact.

In 1873 General George Armstrong Custer, a flamboyant graduate of this institution decamped for the northern plains, and established a summer camp in my hometown of Yankton, S.D.

There is a large billboard on the edge of town now, announcing that with an outsized caricature of Custer saying, “Shore wish I’d stayed.”

There he was taken with an Italian immigrant who was the community’s bandmaster. He persuaded the bandmaster to join the 7th Cav and ride off with him.

The bandmaster agreed, but fortunately, he stopped short of Little Big Horn. Nonetheless, he stayed in the 7th for a number of years before returning to Yankton to establish a successful plumbing business.

His name Felix Vinatierie and 100 years after Custer’s stop in Yankton, his great, great grandson was born in the same community.

The grandson won a place at West Point but decided not to stay,

His name was Adam—and in 2002 he was wearing a uniform but it wasn’t the 7th Cav. He was a New England Patriot—and in New Orleans, he kicked the winning field goal to win the Super Bowl for his team, the first of three Super Bowls he won.

He has gone on to become the greatest clutch kicker in the history of the NFL.

So choose your bandmasters with care. A Super Bowl may be at stake.

Finally, I salute each and every one of you. I will spend every day striving to measure up to the honor you have accorded me.

And I, too, shall be guided by Duty, Honor, Country.

Biography

Born in Webster, South Dakota, on February 6, 1940, Thomas John Brokaw spent his childhood in a variety of places before his family settled in Yankton. After his graduation from that town’s high school, he went to the University of Iowa for one year and then transferred to the University of South Dakota, where he majored in Political Science and worked as a radio reporter. In the same year that he graduated from the university, 1962, he married Meredith Lynn Auld, a former Miss South Dakota.

Tom Brokaw began his television career at KTIV in Sioux City, Iowa, went from there to KMTV in Omaha, Nebraska, and then moved on to WSB-TV in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1966 he joined NBC News, reporting from California, and in 1973 he became an NBC News White House Correspondent. He remained in that position for three years, covering the Watergate Scandal. In 1976 he took over as host of NBC’s Today show, and then in 1981, he began to co-anchor NBC’s Nightly News along with Roger Mudd, eventually becoming the show’s sole anchor in 1983.

His career has been filled with remarkable achievements. He has covered every presidential election since 1968 and moderated several debates among the candidates; he conducted the first one-on-one American TV interview with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987 and followed it up in later years with similar interviews involving Russian Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov and Russian President Vladimir Putin; he anchored The Brokaw Report series of prime-time specials; he co-hosted a prime-time news magazine called Now with Katie Couric; he reported from places all over the globe, from the NBC studios in New York City to the site of the Oklahoma City bombing, from the streets of London and Paris to the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq.

By the late 1990’s Tom Brokaw’s Nightly News had taken first place among the evening news broadcasts, and it held that place until its anchor’s retirement in 2004. That retirement had been announced two years earlier, and finally on December 1, 2004, Tom Brokaw made his last Nightly News broadcast, ending it with a gracious tip of the hat to Brian Williams, his successor.

His books include two tributes to the Americans who came of age in the Great Depression and fought World War II, The Greatest Generation and The Greatest Generation Speaks. He has received scores of prestigious awards and honors, including numerous Emmy Awards, two Peabody Awards, induction into the Television Academy Hall of Fame, and election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Council on Foreign Relations, and he holds honorary degrees from nine colleges and universities.

Tom Brokaw and his wife have three daughters. The couple lives in New York and Montana.