By Desrae Gibby ’91, WPAOG Staff

Using an unwritten formula, West Point coaches have inspired and helped train thousands of cadets to become commissioned leaders of character. What principles would be on the West Point coach’s blueprint for character? It could start, “I am a West Point coach who coaches warrior athletes,” and would likely include an ethos about Duty, Honor, Country and the Army values. Coaching philosophies from each West Point coach would provide additional principles to the formula.

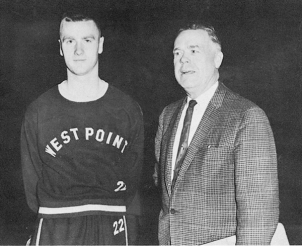

For example, Mike “Coach K” Krzyzewski ’69, the West Point Men’s Basketball head coach from 1975 to 1980, could have the “Krzyzewski Principle,” which emphasizes character, climate, and connections. A relationship-building coach, Krzyzewski once said, “Character drives everything.” Former brigade commander Colonel Mike Guthrie ’78 (Retired), a walk-on to the team in 1976, said Krzyzewski “always ensured a positive team climate” and took time to get to know all his players, even someone who sat on the bench. Proving this, 26 years after Guthrie had graduated, Krzyzewski looked up into the filled stands of a Duke coaches camp, pointed and said, “There are two of my Army players, Mike Guthrie and Matt Brown” (he also recognized Guthrie’s sons when they came to a later basketball camp).

The Saunders Principle: Having vision to sustain the program while training cadets to be proficient, resolute, and resilient.

The coaching practices of Lieutenant Colonel Duston Saunders ’72 (Retired), who was the West Point Army Pistol Team head coach for 31 years (1993—2023) and in 2011 received the Coach K Teaching Character Through Sport Award, could add to the formula. In Saunders’s memorial article for the 2024 TAPS magazine, his B-1 brothers wrote that Saunders was more than a pistol coach, he was a “life coach” and “a leader of character and purpose, [who] treated each cadet with respect and understanding…supported them in hard times and prepared them well to serve the Army and nation.” Saunders’s teams won nine national championships, had an overall record of 211 victories and 54 losses, and included 75 cadets who earned multiple All-American honors. However, those victories didn’t matter as much to Saunders as developing cadets. “[Coach] endeavored to provide the finest tactical training available in the country,” Mitchell Booth ’18 said. “I have yet to encounter a better curriculum to prepare young leaders for combat…Coach cared about mentoring cadets into honest, capable officers more than anything else.” Booth described a time when the team’s best shooter was late for a departure time. All team members held their breath wondering what Saunders would do. The coach chose “the harder right over the easier wrong” and left the team’s best shooter behind, losing the competition yet teaching a lesson. Major Victoria Gramlich ’13, a former team member and its current officer in charge, witnessed Saunders’s characterbuilding coaching techniques: “It is a rarity to find someone so giving and caring with a genuine lack of need for his own selfvalidation,” she said. “Coach Saunders was a one-of-a kind human being, mentor, and inspiration.”

“From day one, Coach…showed he was deeply committed to the development of cadets. Coach was the epitome of soldier for life…[and] a difference maker… .”

— COL Matthew Dooley ’94

Some former team captains described how Saunders taught cadets resolution and resilience. According to Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Dooley ’94 (Retired), Saunders “stabilized” and “rallied” the team after its demotion from corps squad to club squad and “pick[ed] up the pieces” after the destruction of its building in the 1996 range fire. Captain Jack Fagerland ’16 was impressed with Saunders’s dedication to keeping the program “funded and functional” and shared how Saunders helped him “overcome feelings of self-doubt” and taught him “discipline, accountability, and leadership to make him a better officer.”

Dooley summed up Saunders’s influence by saying: “From day one, Coach…showed he was deeply committed to the development of cadets. [He] immediately instituted new training methods and redefined goals for the team…[and] provided that vision and stability to us when it mattered most…Coach was the epitome of soldier for life…[and] a difference maker…When my son, a Class of 2026 cadet, [joined the team] I knew…he would be in the hands of a superb warrior-trainer.”

The Kiesling Principle: Speaking honestly, living fearlessly, and leading by example.

Professor Eugenia Kiesling, another “Coach K” and a rowing celebrity involved in the Yale Title IX protest, was the 2018 Coach of the Year for the Dad Vail Regatta (the United States’s largest intercollegiate rowing event). Kiesling voluntarily coached Army Crew for 29 years, mentoring more than 1,000 cadets during her 22,000-plus hours without pay. “Her passion is teaching novices the sport and inspiring a lifetime of character and athletic growth,” said Colonel Tom Babbit ’99, a former rower and the team’s current officer in charge. “While the loss of her coaching ability will leave a massive hole, her character and leadership development are the most significant losses.”

At tryouts Kiesling never minced words, telling prospective rowers: “Imagine having a vacuum cleaner hose stuck down your throat sucking out your lungs while having sulfuric acid splashed on your legs.” Yet, she also encouraged them, saying, “There’s power [in] pushing through this pain.” Brad Wagner ’16 recalls that Coach K was always perfectly honest. “If another team was better, she told us. Without ever saying the words, she posed the question: ‘Everyone watching expects [that team] to win: what are you going to do about it?’ [That was] the exact fuel we needed.” While in high school, Cadet Ryan Monagle ’27 witnessed Kiesling’s candor when he told her he wanted to row for West Point. She explained he might be frustrated rowing with inexperienced rowers. “She didn’t sugarcoat anything,” he said. “Coach K told me the honest truth.”

“Her passion is teaching novices the sport and inspiring a lifetime of character and athletic growth.”

— COL Tom Babbit ’99,

Army Crew Team OIC

Kiesling invented painful anaerobic interval workouts, which she called “lion taming.” The goal was to conquer the fear of pain. During the “rest” period of these grueling intervals, cadets would hear an oft repeated refrain, “Paddle! Keep rowing!” Cadet Jack Bahouth ’27 called this a metaphor for life. “You’d get to the point where your lungs felt like they were going to explode and your legs started to fail, but you told your brain, ‘No, I won’t stop.’” Cadet Alexa Bernard ’27 stated, “Coach taught me that I am capable of much more than what my mind limits me to.” Kiesling figuratively and literally got in the boat with the rowers. “Coach K is a disciplined warrior who pushes herself just as much as she pushes us,” Bernard said. Kiesling won a gold medal at the 2023 Head of the Charles and often did the workouts she asked her athletes to do.

Captain Jordan Duran ’16, the former team commodore, credits Kiesling for starting her on a “journey of leadership discovery.” Duran applied the “Kiesling Principle” during two commands and fixed-wing MC-12 missions in South America, Africa, and Iraq. Lieutenant Colonel Brian Forester ’04 in the 39th Infantry Regiment at Fort Jackson, South Carolina explained that Kiesling’s speech about putting in the necessary work stuck with him, especially the words: “Worthy to Win.” “I use that phrase regularly,” he says, as a parent and as a current battalion commander.

“Unforgettable,” is how Captain Courtland Adams ’15 described Kiesling. “There are very few individuals who’ve left such a profound mark on my life…her devotion to molding novice rowers into lieutenants is what makes Coach K an Army Crew legend.”

The Crowell Principle: Demonstrating respect, self-control, and competence while fostering trust and cohesion.

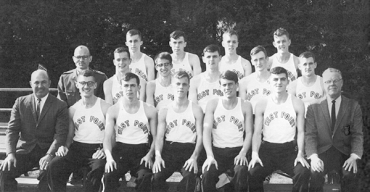

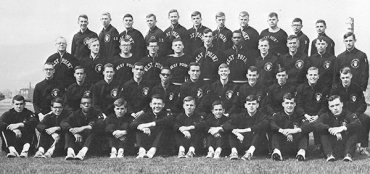

Another character-building coach was Carleton Crowell, a hall of fame head coach of Army’s Track and Field (1951–75) and Cross Country (1954–74) teams. “He always had time for you,” explained Colonel Lee Outlaw ’68 (Retired), broad/triple jumper and long sprinter. “He was the best at mentoring and teaching mutual respect [which made] practice a refuge.” Former team manager Colonel Paul Joseph ’68 (Retired) agreed, saying, “[Crowell] was a gentleman and treated everybody with respect… even if you weren’t a star.” Former team captain Colonel Greg Camp ’68 (Retired) added, “He had your best interests in mind…You wanted to honor the effort he had put into you.” All three alluded to Crowell’s self-control, contrasting him with more temperamental contemporaries. Crowell created a cohesive team. “The team was a brotherhood,” Outlaw remarked. “If you didn’t have a good father, Coach was a father to you,” added Camp. “If you had a good father, Coach was another father for you.” James Warner ’67, mid-distance runner, especially looked to Crowell as a father figure and appreciated his fatherly advice. Warner chose Army over Navy because he trained at the field house in high school and saw firsthand Crowell’s quiet way of building confidence. They all remember happy times at the Crowell home, where a wall was signed by Crowell’s athletes, making them family. According to Outlaw, Crowell’s genius was in “taking whatever athletes he was given,” “turning them into a team,” and “helping them reach their potential”—so much so that his teams dominated on the East Coast during the 1960s.

“He always had time for you. He was the best at mentoring and teaching mutual respect [which made] practice a refuge.”

— COL (R) Lee Outlaw ’68

Crowell’s athletes emulated his leadership in the Army. Joseph said Crowell knew them well and ensured they had the necessary resources. Joseph, who likewise cared for his soldiers in all his positions, from commander in Vietnam to defense attaché in Panama, said, “[I spent] as much time as possible with [my soldiers], so that I knew more about them and their circumstances.” Warner applied the “Crowell Principle” while commanding in Vietnam and stayed connected with his soldiers long after the war. Camp, who commanded at the brigade level, stated, “I sought to be a leader in Crowell’s mold.” In September 1975, Camp, a West Point math instructor, ran with the Cross Country Team. Crowell cheered him on as he hung with some young All-Americans. The next day, Crowell suffered a fatal heart attack. Camp paid tribute to his amazing mentor by serving as his pallbearer. The chapel was filled as West Point honored the coach who inspired cadets for 25 years. Crowell Track in Gillis Field House memorializes him, and he is in the West Point Cemetery close to some former athlete “family members,” including astronaut Ed White ’52 and Olympian Ronald Zinn ’62.

The Alberici Principle: Teaching accountability and fortitude while showing loyalty and commitment to relationships.

In March 2024, for the first time in Academy history, the Army West Point Men’s Lacrosse Team ranked No. 1 in national polls. Jack Emmer Head Men’s Lacrosse Coach Joe Alberici also stands out for other reasons. Lieutenant General Kenneth Dahl ’82 (Retired), a lacrosse alumni leader, stated that, for 18 years, Alberici has been preparing cadets for the toughest Army assignments. Many players agreed and gave examples of values Alberici had taught them that they now use in their careers. Major Patrick Mulholland ’11 said Alberici taught him and his teammates that they were “part of something larger than themselves…West Point” and stressed duty and integrity through “extreme ownership.” Mulholland continued, “Whenever we lost, Coach A shouldered the burden, blaming himself; when we won… [he] sang our praises.” According to Captain John Ragno ’18, Alberici demonstrated “unwavering loyalty” when he recruited him as promised, despite Ragno’s ankle injury. “What separates Coach from others is his intentional and unrelenting commitment to his relationships,” explained First Lieutenant Bobby Abshire ’22, adding, “[He] continuously reaches out to check on me.” Jake Murphy ’09 also shared, “[Alberici] teaches his players good practices for post-Academy life, which was evidenced when I hit an IED in Afghanistan and later received a helmet signed by each of the players.”

Alberici is inspirational and pushes his players to develop fortitude. Historic team mottos, “Family, Toughness, Tradition!” and “Hungry and Humble,” highlight this. Mulholland said these mottos gave him “a personal and organizational mindset that [he] brings to every military unit.” Dahl said many former lacrosse players who served in Iraq and Afghanistan “credit Coach A for preparing them for the experience.” While deployed to Afghanistan as a 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment platoon leader, and, while in Syria and Iraq, Ragno used what Alberici had taught him about “resilience and camaraderie, lessons learned during intense January practices at Michie Stadium and early morning weekday workouts at Kimsey,” which showed him “that any team can surpass their perceived limitations.”

“[Alberici] teaches his players good practices for post-Academy life, which was evidenced when I hit an IED in Afghanistan and later received a helmet signed by each of the players.”

—Jake Murphy ’09

In Poland, Abshire is currently using the “Alberici Principle” to motivate his soldiers. “I am charged with creating buy-in, and I routinely fall back on how Coach would rally 60 guys on cold nights in Michie.” Major Alex Gephart ’10, a Ranger operations officer, has found the lessons Alberici taught to be valuable on his multiple deployments. He said Alberici taught “the most important thing to win was the will to prepare” (Bobby Knight, West Point Men’s Basketball head coach [1965–72], said the same and would have explained such preparation with: “Drill! Drill! Drill!”). All these former Lacrosse Team players have found the “Alberici Principle” useful in motivating their soldiers to focus on the mission.

Added together, the principles that these coaches practiced and passed on to their athletes could fashion the following West Point coach’s formula for developing character (perhaps echoing the Soldier’s Creed):

- I am a West Point coach who coaches warrior athletes.

- I live and teach West Point and Army Values, preparing cadets to lead soldiers.

- I emphasize character, climate, communication, and connections.

- I sustain the program and train cadets to be proficient, resolute, and resilient.

- I candidly teach courage and lead by example.

- I demonstrate respect, self-control, and competence, fostering trust and cohesion.

- I show loyalty and take responsibility for my team while teaching fortitude and focus.

- I prepare athletes to win with discipline, detail, and drill, drill, drill!

West Point coaches not only develop soldiers and leaders of character, they reflect the character of the institution. General Douglas MacArthur, Class of 1903, an avid supporter of West Point athletics, would have agreed. An April 18, 1939 letter, in which MacArthur elaborated on his “fields of friendly strife” couplet, supports such a creed: “[Athletics produce] in superlative degree the attributes of fortitude, self-control, resolution, [and] courage…[which are] completely fundamental to an efficient soldiery.” Ergo, every cadet an athlete and every coach an inspiration.

Hear more from West Point coaches on the WPAOG Podcast by searching for additional coaches (Monken, Riley, Sherman, Tumolo) by name.

What do you think? Click here to answer four questions.