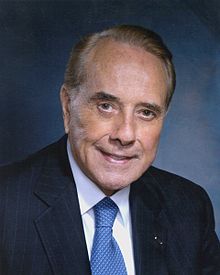

A statesman of great distinction, Robert J. Dole has made a lifetime of remarkable contributions to the Nation and its citizens. His reliance on time-honored values, which is manifest in both word and deed, has characterized every facet of his life. He is a living exemplification of the ideals expressed in West Point’s motto—Duty, Honor, Country.

Even before Bob Dole entered in his career of public service, he had shown his bravery and strength of character in World War II combat. His heroic attempt to rescue a downed soldier earned him the Bronze Star, along with two Purple Hearts for the savage wounds that he sustained, and he courageously endured the painful recovery and rehabilitation process that followed for over three years.

As an elected official, he placed the concerns of his fellow citizens and the vitality of the Nation at the forefront of his own concerns for over four decades. Serving at the state level, in the United States Congress, and the United States Senate, he compiled an unmatched record of achievements. And he continued his selfless service once he had retired from public office by tirelessly devoting himself to a wide array of worthy causes.

The superb accomplishments of this son of the Midwest and benefactor of the entire Nation have been both wise in their aims and positive in their effects, earning him a prominent place in the annals of American history. Accordingly, the Association of Graduates is both pleased and honored to present the 2004 West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award to Robert J. Dole.

Article

Last week, on Wednesday, 29 September 2004, the West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award was presented to an “old soldier,” Senator Robert Dole. It was a cool, somewhat overcast, breezy day, unlike many previous Thayer Award days that tended toward the sunny, hot and humid.

The schedule remained the same as in the past: reception at the West Point Club for the recipient and family, movement to The Plain for the Cadet Review, dinner in Washington Hall, and a special reception following at the Superintendent’s quarters. There were, however, some major changes in execution. Senator Dole was unable to fly into Stewart Field until late in the afternoon, so he was unable to attend the reception. Nor was his spouse, the other Senator Dole, able to attend at all because of commitments related to her office. In deference to his physical condition, Senator Dole chose to sit in the Superintendent’s box during the entire ceremony and was not required to troop the line in a jeep. Nor did his schedule permit him to attend the traditional by-invitation reception at Quarters 100 following the dinner.

Nevertheless, none of these departures from the traditional award ceremonies diminished the occasion in the least. Nor could the fact that merely gaining access to Washington became somewhat of a challenge. The entire newer front half of Washington Hall was cocooned in canvas for renovations that forced all to enter via the sally ports to the “old” half of the mess hall. This portion already had been renovated and sported brilliant reds on the ceiling of the old regimental wings and dark wood beams, except for the blue ceiling with white beams of the center wing where the Corps Squad teams congregated in an earlier day.

One could tell that this would be a memorable evening as soon as the pass-in review was completed and Senator Dole joined the reviewing party and brigade staff for photographs. He clearly was in his element, shaking hands, speaking with the young cadets, making jokes and comments. The warmth carried on over to the rest of the evening. To the delight of the cadets, Senator broke off from the official party to visit with many of them at their tables after he entered the mess hall, again shaking hands, making humorous comments, and chatting along the way.

Senator Dole had a prepared speech, but he used very little of it. Instead, his comments digressed on a number of subjects. He joked about appearing in various advertisements on television, and he waxed humorously about raising money for the National World War II Memorial. He said that before calling to thank a donor who had sent in a check for $1 million, he deposited the check first. The Senator said he learned that from being a politician. He even made himself the butt of a joke about how someone from the Clinton campaign changed his bumper sticker that read “Dole in ’96” to “Dole IS 96.” He noted the irony of a Kansan (“not many Kansans ski”) being assigned to the 10th Mountain Division and warned of both the dangers of a lieutenant with a map and bullets marked not with your name but addressed simply “To whom it may concern.”

He told of how he was wounded while attacking a hill in Italy as an infantry platoon leader not that long out of Officer Candidate School. He spoke of receiving machine gun fire from the left flank that struck his platoon runner and his efforts to crawl forward to help the wounded soldier. Soon, Dole himself was a casualty, struck in the shoulder and back, and it would be nine hours before he could be evacuated to medical facilities.

He also noted that when he was in college before the war, a professor had suggested he stop wasting time and join the Army instead-so he did. He praised the medical personnel who encouraged him to accept his later physical condition and continue on with his life. And he also noted that, upon his return to school after rehabilitation, he was unable to write and had to use a primitive recording machine during the lectures. As a result, he had the best notes in his class-thus making him very popular around exam time.

He also commented seriously upon his work as the national chairman of the recently dedicated National World War II Monument in Washington, DC. Drawing upon the phrase applied to his wartime generation, he said that the current “greatest generation” is now serving in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Soon the dinner and speeches were over, the Alma Mater was sung, the final benediction given, guests spilled out into the cool, evening air, and the cadets returned to their barracks. As they departed the mess hall, the cadets were not talking about sports, homework or the next big paper due. Instead, they were talking about Senator Dole and his speech. The 2004 West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award recipient may not have been able to attend the various receptions or troop the line, but his words had struck a chord with the Corps. And then the “old soldier,” senator, and presidential candidate departed West Point without further ado.

/s/

Your humble servant,

J. Phoenix, Esquire

Speech

Remarks by Senator Bob Dole

Upon receiving the Sylvanus Thayer Award

West Point – 29 September 2004

Thank you very much, Colonel Hudgins, for that generous introduction. Let me also thank General Lennox and the entire corps for the spectacular parade. Quite a thrill for a second lieutenant from Russell, Kansas. Almost makes up for that inaugural parade I never got to review. I wish I possessed the eloquence to do justice to this occasion but I’m afraid you will have to settle for some midwestern plain speaking…you know, there is a story about a platoon Sergeant and his leader who were buttoned down in the field for the night. After a while, the Sergeant looks up and says, “When you see all the stars in the sky, what do you think, sir?”

The Lieutenant ponders this for a moment, “Well,” he says, “I think of how insignificant we are in the scheme of things – how small a piece of such a grand design. What’s more, I can’t help but wonder whether anything we do means anything or makes any difference. Why do you ask, Sergeant? What do you think of?”

“I think,” says the sergeant, “somebody stole the damn tent.”

Any visitor to West Point stands on ground hallowed by two centuries of service and sacrifice. Here the value of education is measured by one’s education in values. Above all by the three words that define this place, and which for over two hundred years have defended these shores. Duty. Honor. Country. No civilization that neglects these words can long be called civilized. Older than the republic, timeless as patriotism itself, they offer a code to live by – and a creed worth dying for. In a world of accelerating change, they do not change. For they are the foundation of character, both individual and national.

The Long Gray Line stretches back more than 200 years, further still if you take into account the frustrations General Washington experienced in fighting the Revolutionary War with militia instead of a professional army. You keep company with vanished generations whose customs, language, and ceremonies have always made West Point a parallel universe of sorts. Back in the 1920’s Douglas MacArthur was a reform-minded superintendent who emphasized athletic competition and shook up the curriculum by adding subjects like economics and political science. Before he was done, MacArthur had moved reveille up an hour, allowed each cadet to carry five dollars a month spending money, and curtailed hazing of plebes during Beast Barracks.

So much reform was bound to raise the hackles of the Old Guard on the academic board. Since the superintendent only had one vote on the board, MacArthur the strategist fell back on tactics. He simply stopped convening meetings of the board at eleven in the morning, and started holding them at four-thirty in the afternoon. “I want them to come here hungry”, he explained, “and I’ll keep them here that way until I get what I want”.

I promise I will make no such demands on you this evening. In a long life, I have received many honors. Few, if any, have meant more than this award that bears the name of the Academy’s true father—and that admits me to the rarified company of MacArthur and Bradley, Eisenhower and Reagan and Bush. Although I never became your Commander in Chief, I believe I am your comrade in arms. For whatever offices I may have held, and whatever titles were affixed to my name, the greatest honor of my life has been to wear the uniform of the United States of America.

That is one thing all of us have in common. There are others: pride in our service; gratitude for the privilege of serving, and a fierce resolve to preserve all that makes life itself worth living. At West Point, nothing is supposed to be easy. That includes self-appraisal. In the twilight of his career, Douglas MacArthur said something that we might all reflect upon. “Could I have but one line a century hence crediting a contribution to the advance of peace,” he said, “I would gladly yield every honor which has been accorded by war.”

For once the great general was guilty of understatement. Because in the end, who contributes more than the soldier to the maintenance of peace? It is his strength that permits the diplomats to fashion their agreements—the politicians to construct their alliances—and his countrymen by the millions to pursue their own dreams. The nation’s security rests on the soldier’s sacrifice.

As a soldier first, and a politician second, I guess you could say I straddle both worlds. As we meet America is engaged in intense debate over the course of our country and its global mission. Every four years we are reminded that democracy can be fickle, often noisy, sometimes chaotic. From time to time it is claimed that generals like nothing better than refighting the last war. I don’t know about that: judging from recent headlines I would say that it isn’t the generals who are preoccupied with yesterday’s battles – but the journalists, the pundits—and the Kinko’s operators.

This is ironic, as well as unfair, since if there is anyone who has learned the lessons of Vietnam, it is our armed forces. As evidence, I could submit their performance in the Gulf War, Afghanistan, and, yes, Iraq. Age may or may not bestow wisdom. But experience offers its own education. With enough experience comes perspective – the next best thing to wisdom. The army was my classroom. Before I joined its ranks I lived in a narrow world, geographically speaking. Before Pearl Harbor I had never flown in an airplane or ridden on a bus. I had never traveled east of Kansas City, never been exposed to Brooklyn’s teeming diversity or the lonely majesty of the Louisiana bayou.

Of course, I had never been shot at either, though I have since come to regard that as good training for a political career. Perhaps some of you underwent similar culture shock when you first joined the Academy. Like most of my generation, I grew up fast after December 7, 1941. I left the University of Kansas to obtain a different kind of education. Along with millions of other young men, I put aside the study of history to make some. My West Point was Fort Benning in Georgia, otherwise known as the Benning School for Boys. My post-graduate training came in the mountains of northern Italy. Now I don’t know if there are any Jayhawks here…but take it from me, we Kansans grow the best wheat in the world. We’re also known for our corn, soybeans and sunflowers. What we’re not known for is our mountains. Consequently not many Kansans ski.

So where did I get assigned? To the Tenth Mountain Division, a crack unit of Olympic skiers and Ivy League athletes. Other lessons in military logic followed. First off, I learned that you should never draw fire; it only irritates everyone around you. I learned that the most dangerous thing in a combat zone is an officer with a map. Most important of all, I learned that it’s not the one with your name on it you have to worry about – it’s the one addressed “to whom it may concern.”

In an army, you treat the next soldier as if your life depends on him. Because often it does. William Tecumseh Sherman was nothing if not loyal, especially when speaking of his best friend. “Grant stood by me when I was crazy,” said Sherman, “and I stood by him when he was drunk, and now we stand by each other.” Now you know why Sherman never went into politics.

Of course, I learned other things as well. I learned that much of war is organized boredom, followed by disorganized terror. Sometimes it’s the other way around. Faith and fear are the constant companions of any soldier. Sixty years on, you never quite get the chill of northern Italy out of your bones. The whine of the carbine is as fresh as the horror of seeing your newfound best buddy go down. But the horror is far outweighed by the heroism. What is it that makes soldiers out of raw recruits, that sends them up a hillside studded with mines and raked by enemy fire? Duty. Honor. Country.

Eventually, you turn your memories into memorials—not for the dead—their sacrifice is already known to God—but so that the living might draw inspiration for whatever challenges may lie before them. The Bible tells us that old men plant trees, precisely because they know they won’t be around to enjoy their shade. The World War II Memorial we dedicated earlier this year is just such an act of faith. The term war memorial is actually something of a misnomer. It isn’t war we are commemorating, much less celebrating. “I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality and stupidity.” The words are Dwight D. Eisenhower’s; the sentiments those of virtually every man or woman, regardless of rank, who has experienced the paradox of military combat.

On the one hand, war represents the ultimate failure of mankind. Or at least of the politicians and diplomats entrusted with keeping the peace. Yet it also summons the greatest qualities of which human beings are capable: courage beyond measure, loyalty beyond words, selflessness beyond imagining.

It is those qualities we imperfectly honor in bronze and granite.

For younger visitors, the World War II Memorial will be a place of discovery. For others, inevitably, it will call forth painful recollections. For everyone, we hope, it will be a place to reflect on what the Corps has always known – that liberty must be defined, and defended, by each generation in its own way.

In recent years it was fashionable in some quarters to suggest that the MTV generation somehow lacked the courage or character that drove the heroes of Iwo Jima and Omaha Beach. Tell that to the heroes of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Tell it to the men and women who, even now, are carrying the fight to the enemy in Baghdad’s back alleys. Think of all they have accomplished.

They have liberated Afghanistan from the zealots in their caves. They have freed Iraqis from a strutting psychopath and his regime of torture chambers and acid baths. They know better than anyone that risks remain, yet they put their lives on the line because they know that to live without freedom is hardly living at all.

There can be no freedom without Duty, Honor, Country. Ancient virtues, never more desperately needed than in these modern times. For if the world seems smaller than before, it is no less dangerous. In this young century, we all wish that tyrants would retire from the field and that no young American would ever again have to confront a dictator in the desert or a terrorist with access to nuclear weapons. But wishful thinking is no substitute for national will. You are the instruments of that will. You are the vanguard of American power. You are also the embodiment of what that power is projected for.

Riding the crest of events, we are not the same people who slumbered through the deceptively placid decade of the 1990s. On a crystal day in September, 2001 terror made alliance with technology, and mass murder joined hands with martyrdom. Overnight America’s mission was redefined, along with our mandate to combat international terrorism wherever it lurks. President Bush told us at the outset that this is a different kind of war we are called upon to wage. A war without front lines. A war in which progress will not be measured by moving pins on a map. The battles of this war will be fought in cyberspace as well as the bazaars of Kabul and the treacherous lanes of Fallujah.

But seen in perspective, even this war is part of a larger, longer struggle. If the overriding cause of the 18th century was to establish popular government in an era of divine right; if the moral imperative of the 19th century was to abolish slavery and reaffirm the sacred bonds of Union; then in the 20th century it fell to over 16 million citizen-soldiers to preserve democratic freedoms at a time when genocidal dictators threatened their very existence.

Now, in the 21st century, a new generation of West Point’s finest confront a ruthless enemy in combat that may last for years to come. It is your privilege, as soldiers of democracy to carry our flag, preserve our liberties, and protect our homes. And to do all this in the name of Duty, Honor, and Country.

May God bless you all. And may God bless America.