By Erika Norton, WPAOG Staff

West Point is known for developing leaders of character, and its graduates who go on to serve in the medical field are no exception. There is a rich history of West Point graduates becoming physicians, making an impact in all areas of healthcare, both on and off the battlefield.

From operating on presidents (such as Dr. Thoralf M. Sundt Jr. ’52, who operated on Ronald Reagan) to heading Army hospitals and serving as surgeons general, the 1,092 known doctors of the Long Gray Line have always healed from the front.

West Point magazine spoke to a few of these physicians. While their journeys differ, each believes their education at West Point helped prepare them for their service in the medical field.

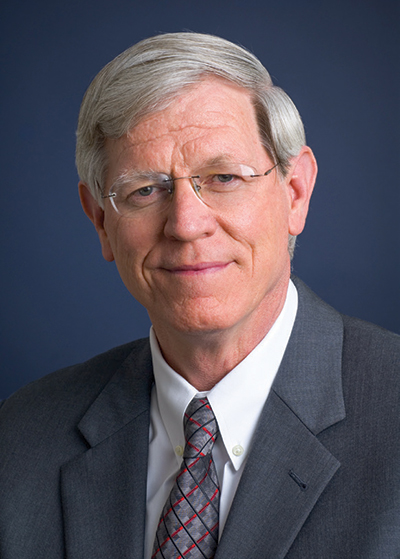

Colonel Victor Garcia ’68 (Retired)

Garcia is currently a professor of Surgery and Pediatrics at the UC School of Medicine and a pediatric surgeon at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, where he founded the trauma department. After graduating from West Point in 1968, Garcia spent a year in Korea and then graduated from Ranger School before being assigned to Germany. While there, he applied to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and got in. “I felt that, as a physician, I could serve both my purpose and my obligation by healing people,” Garcia said.

West Point prepared him well for the medical profession. He learned to hold himself to the principles of honesty and integrity while serving on the Cadet Honor Committee. As in the Army, both of these values are instrumental to being a doctor, according to Garcia. The other skill Garcia learned from West Point is teamwork. As a cadet, he saw how people with different backgrounds and different life experiences needed to work together to accomplish a mission. The same goes for surgery, except the mission involves saving a life.

Garcia, who was recognized as a Distinguished Graduate in 2019, said that when he looks back at his training at West Point and in the Army, he learned how to push past obstacles, both external and internal. In 1964, when Garcia entered West Point, there were only five minorities in a class of more than 1,700. Through the challenges at West Point and at Recondo training and Ranger School, he realized there was really nothing that he couldn’t achieve; it was actually his own self-imposed limitations that he needed to rise above. “If you think you can’t or you think you can, you’re right,” Garcia said. “My West Point and early Army experiences helped me appreciate that there’s really nothing that I can’t achieve, not just as an individual, but as a leader.”

“I felt that, as a physician, I could serve both my purpose and my obligation by healing people.”

— COL (R) Victor Garcia ’68

Garcia said that, sadly, the injuries that he sees in children are similar to the injuries he saw in soldiers at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, namely gunshot wounds. He said a turning point in his career occurred when a 12-year-old died in his hands from a lethal gunshot wound to the chest.

“Despite having the best pediatric trauma program in the country, with all that expertise and all the technology, that child died, and it became apparent to me that my responsibility was to prevent injuries from occurring and not limit myself to what I could do in the operating room with the skills as a surgeon,” Garcia said. “This experience resonated with me as being similar to the mission at West Point, training to be leaders in times of war and of peace.” Going further, Garcia said, “You’ll see former West Point graduates with all sorts of distinguished accomplishments, but, for me, it was addressing inequities and disadvantages that persist in this country that particularly affect marginalized people, which I think is in line with the purpose of West Point.”

Colonel Bill James ’72 (Retired)

James is currently an emeritus professor in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. When he went to West Point, James hadn’t even thought about medicine, nor did he think there was a way to go to medical school through West Point—that was until a fortuitous moment in one of his science classes. James was in his thermodynamics class, and a cadet asked the instructor one day: “You’re the medical school liaison officer for us, aren’t you? Tell us about the program.” Amazed by what he had heard, James went to his then-girlfriend’s house for Christmas and said to her, “I’m good at science and math and I want to be around people, so this seems like something I should consider.” He decided to pursue medicine then and there.

At the time, by law, only one percent of a West Point class could go directly to medical school after graduation, and James just missed the cut. He also still needed several prerequisite courses since he decided to apply to medical school late into his cow year. James reapplied the next year through a program that existed at the time that allowed a small number of active-duty soldiers to go to medical school. He was accepted into the Indiana University School of Medicine with the provision that, during summer school, he would take some of the prerequisite science courses he still needed. James decided to go into dermatology after talking to a friend who was a dermatology fellow. He liked that he would get to serve patients of all ages and that dermatology is a combination of both medicine and surgery, given that many skin conditions can predict a patient’s internal health.

According to James, the character traits instilled in cadets—such as holding oneself accountable for one’s performance, hard work, and being goal-oriented when working with a team—helped prepare him for his career in dermatology. His military education and training also helped him, specifically his residency at Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco. “Early in my residency I was taking care of a patient with a leg condition, and I think my knowledge of some of the tactics used during the Vietnam War helped me make a diagnosis that hadn’t been suggested before,” he said. “The patient had a shrapnel wound from a landmine that caused an arteriovenous fistula, which was then able to be cured.” James was also Keller Army Hospital’s dermatologist for two years and says that his knowledge of cadet life helped him take better care of cadet patients. He helped a cadet who was in a training accident where his machine gun misfired and blasted back into his face and carbon particles implanted into his skin. He also discovered that a certain chemical being used on cadets’ feet to toughen them up was actually causing blisters and other allergic reactions.

Later, as chief of dermatology at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, his knowledge of how a soldier’s skin can incapacitate a soldier on the battlefield became invaluable. “I took care of soldiers who brought back infectious diseases from their overseas assignments,” James said. “My knowledge of their occupational exposures allowed me to narrow down possible conditions that might have escaped other doctors.”

James says his favorite part about being a physician is the relationships he’s built, both with patients and his students. “I’ve taught a lot of residents and fellows, and being able to see their contributions over the years is certainly satisfying,” James said.

Lieutenant General Nadja West ’82 (Retired)

West grew up in a military family. When deciding her career path, she felt the medical field was a way for her to combine her desire to serve, her interest in science, and her desire to take care of others, especially soldiers and their families.

While attending West Point, her father became seriously ill and went to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for treatment. Seeing the inner workings of the hospital further solidified West’s desire to go to medical school, and a chance encounter with a plastic, reconstructive, and hand surgeon Dr. Alan Seyfer ’67 in the hospital’s elevator the summer before her firstie year inspired her to go right after graduation. West told Seyfer that she wanted to go to medical school but that she’d probably wait because of the difficult application process and because of her dad’s situation. According to West, Seyfer gave her the inspiration she needed when he said: “Why don’t you apply? What’s the worst that can happen? They say ‘no.’ And if you’re going through West Point, that’s pretty tough, so I’m sure you’ll be able to do it.” Seyfer encouraged West to take the MCAT and see what happened. He later came and visited her dad, and West ended up doing a summer research project with Seyfer.

West not only got into the George Washington University School of Medicine but went on to serve as a Medical Corps officer at Fort Benning, Georgia. She deployed with the 197th Infantry Brigade, 24th Infantry Division for Operation Desert Shield and was attached to the 2nd Battalion, 69th Armored Regiment for Operation Desert Storm. She also deployed to the former Yugoslavian republics of Macedonia and Kosovo, serving as the deputy task force surgeon for the 1st Armored Division. In 2013, West became the first Black woman to become a major general in Army medicine, as well as the first Black woman to become a major general in the active-duty U.S. Army. She was promoted to lieutenant general in 2015 upon being appointed the 44th Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, becoming the highest-ranking West Point woman graduate at the time. “If it hadn’t been for West Point, I don’t think I would have done any of those things,” West said. “I worked hard, and I studied hard, so I would have done something, but I don’t know about being Surgeon General of the Army.”

West, who was recognized as a Distinguished Graduate in 2022, said the discipline she learned at West Point to overcome really challenging times—as part of only the third class of women at West Point—allowed her to expand her skill set and later do things that she never would have done. All the opportunities she had, including going to Air Assault School and Airborne School, helped push her out of her comfort zone. “It gave me a better understanding of the people that I would support,” West said. “There’s no requirement for a doctor to go to Airborne School or Air Assault School, as you just need to be a competent physician and take care of patients; however, the inspiration I had from West Point and being immersed in a military culture and environment contributed to every position I had throughout my military career.”

When someone asks West how she selected the different steps she took to get to the point of Surgeon General, she says she didn’t map anything out; she just went wherever the Army needed her. For example, she went to Korea right after being in Germany for four years because the person who was slated to go couldn’t and they needed a dermatologist. “If that’s what is needed, that’s where I’ll go,” West said. “That’s my duty, and it’s all about Duty, Honor, Country.”

Listen to Lieutenant General Nadja West ’82 discuss her story on the WPAOG Podcast.

Colonel Benjamin “Kyle” Potter ’97 (Retired)

Potter had always planned on going to medical school, but when he got accepted to West Point, he decided he would serve for five or six years before doing so. His plebe year at the Academy was tough, but somewhere in the middle of his yearling year he realized that he enjoyed the discipline and challenge to excel in a rigid environment and decided he wanted to go straight to medical school. The problem was he didn’t have the prerequisites needed. If he was going to get in, he needed to revamp his whole academic schedule for the next two years, which is what he did. He even ended up taking organic chemistry as a firstie in a class full of yearlings, after he had already taken the MCAT.

Even after all that, Potter was conflicted about going straight to med school and not becoming an infantry officer like his friends. He applied to only three medical schools and decided to let the chips fall where they may. He was one of the two percent of graduates who, by law, could go straight to medical school, being accepted to the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine.

Originally, Potter had no interest in surgery due to the long hours involved; however, after spending only one week with a tumor surgeon operating on bone sarcomas, he was sold. “I thought he did the coolest surgery,” Potter said. “He operated all over the body, and they were complicated surgeries that other surgeons were scared of.” Potter once again revamped his whole schedule and went into orthopedics. When 9/11 happened, Potter was an intern at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Soldiers from Afghanistan and Iraq started coming in with serious combat casualties, and there were not many orthopedic trauma surgeons who had the expertise to take care of patients with limb loss. According to Potter, in theory, amputations seem like an easy surgery to perform, but, in reality, there can be a lot of complications and things that could go wrong. Don Gajewski, the orthopedic oncologist at Walter Reed at the time, stepped up and started taking care of these patients, and Potter stepped up to assist and learn. “I liked working with him and appreciated that this was a neglected population of orthopedics,” said Potter, who decided to become a tumor surgeon with a unique skillset. Potter was fortunate enough to not only go into orthopedics but was allowed by the Army to do a tumor fellowship. He returned to Walter Reed, immediately took over for Gajewski, and was the “tumor and amputee guy” for the next 16 years. As director for surgery at Walter Reed, he operated on more than 1,000 injured service personnel returning from duties overseas, including more post-9/11 U.S. war casualties with limb loss than any other military surgeon, according to Penn Medicine News. “It’s been the honor of my life and certainly my professional career to be able to apply the skills I have to such a deserving patient population, literally America’s sons and daughters in uniform.” At one point, Potter even took care of his West Point classmate Daniel Gade, who lost his right leg at the hip.

“I feel like I have a job where I get to take care of our nation’s heroes and be a servant’s servant, and that’s been the story of my career.”

— COL (R) Benjamin “Kyle” Potter ’97

After retiring from the Army last year, Potter, who recently won the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine’s Army Hero of Military Medicine Award for his leadership in combat casualty care, was named “Chair of Orthopedic Surgery” at Penn Medicine. He attributes West Point for helping prepare him to lead by example. “I’ve never been a big screamer or yeller or someone who says, ‘You’re going to do this because I said you have to do it’; rather saying, ‘We’re going to do this because this is the right thing to do, it makes sense and I’m going to do it with you,” said Potter, perhaps channeling “Schofield’s Definition of Discipline” from his old Bugle Notes. “I feel like I have a job where I get to take care of our nation’s heroes and be a servant’s servant, and that’s been the story of my career.”

Major Kiley Hunkler ’13

Hunkler majored in Engineering Psychology at West Point but completed the pre-med courses not part of her major in order to apply to medical school as a cadet. As a cadet, she had the opportunity to travel to Ghana with other cadets and USMA associate professor Dr. Alan Beitler ’77, a general surgeon with specialized training in surgical oncology. The trip proved to be very influential. “Dr. Beitler showed us the complexity and excitement of the operating room,” Hunkler said. “His love of helping patients was infectious and solidified my interest in pursuing the medical field—he even removed my own stitches on the trip with the other cadets ‘assisting’ him!”

Thanks to the encouragement of several mentors within the USMA Graduate Scholarship Program, Hunkler not only applied to medical school but also applied for a Rhodes Scholarship, for which she was selected in December of her firstie year. She graduated from West Point in 2013, was able to defer medical school for two years, and went on to complete her studies at the University of Oxford. She started medical school at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 2015. Hunkler completed her residency training in gynecologic surgery and obstetrics at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and is now conducting fellowship training in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. “I have five sisters and completed a master’s in women’s studies as part of the Rhodes, so I think caring for women was a natural fit,” Hunkler said. “Reproductive medicine is a fast-moving and intellectually stimulating subspecialty, and helping patients build their families is truly a special privilege.”

Hunkler says she will always be grateful for her West Point education because the opportunities and mentorship she received led her to medicine and prepared her for a rewarding career. Medical training is an exercise in working with constantly changing teams, according to Hunkler, which is fairly similar to the West Point environment. “Chief residents must engage in peer leadership, which felt less intimidating thanks to my experiences at West Point,” she said. “I think my experiences at West Point also help me relate to my patients,” Hunkler said. “Many of my patients are very readiness-focused and have career goals they are trying to balance, and understanding those priorities helps me to strategize their care.”

According to Hunkler, the best parts of her job are her patients and colleagues. “I love taking care of patients in the clinic, the operating room, and in labor and delivery,” she said. “It’s a very personal space, as my own department delivered both of my children. It’s what makes military medicine so special. We take care of each other’s families and are therefore very invested in each other’s training and successes.”

The Next Generation

Twenty-three members of the Class of 2024 who were selected for the Pre-Medical School Scholarship are now in medical school continuing the legacy of healing from the front. Endorsed by the United States Military Academy Medical Program Advisory Committee for their commitment to research, clinical exposure, and volunteer work, these graduates will go on to serve as the next generation of Army medical doctors.

Is There a Doctor in the Line?

Are you a physician? Let us know! Click here to participate in WPAOG’s “Physician Survey,” the information will be printed in the USMA Graduate Physician Compendium and made available to fellow graduates in the medical field, as well as to current cadets pursuing entrance to medical school.

Photo 1: Shutterstock. Photo 2: COL (R) Victor Garcia ’68 currently serves as a pediatric surgeon at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, where he founded the trauma department. He is also a professor of Surgery and Pediatrics at the UC School of Medicine. Photo 3: COL (R) Bill James ’72 is an emeritus professor in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Photo 4: LTG (R) Nadja West ’82 served as the 44th Surgeon General of the U.S. Army and as commanding general of the U.S. Army Medical Command. Photo 5: COL (R) Benjamin “Kyle” Potter ’97 served as director for surgery at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he operated on more than 1,000 injured service personnel with post-9/11 U.S. war casualties. Photo 6: MAJ Kiley Hunkler ’13 (center) completed her residency training in gynecologic surgery and obstetrics at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and is now conducting fellowship training in reproductive endocrinology and infertility.

What do you think? Click here to answer three questions.