By LTC (R) David Siry ’94, Guest Writer

Spanning the classes of 1941 to 1970, 333 West Point graduates died during the Vietnam War, which lasted from the formation of MAAG Vietnam (Military Assistance Advisory Group) on November 1, 1955 to the withdrawal of the last American combat troops on March 29, 1973. In 2012, the United States of America Vietnam War Commemoration was authorized by Congress, marking a 50th anniversary commemoration period, and the Vietnam War Veterans Recognition Act of 2017 designated every March 29 as National Vietnam War Veterans Day. The story of the Military Academy and its graduates is intertwined with the story of American involvement in Vietnam.

During the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, American involvement was limited to advisors working with the South Vietnamese military (ARVN—Army of the Republic of Vietnam). Victor Hugo ’54 spent 18 months (1955-56) training ARVN officers in the Philippines and in Vietnam. Volney Warner ’50 served as a province senior advisor in 1963 and noted that, in the beginning “you thought you could do more good for humanity in six months probably in that part of the world than you could in the rest of the world in a lifetime,” but over time he came to realize that “it’s hard to tell who’s on what side.” Advisors continued to serve with ARVN forces throughout the war, even as American troops were withdrawn. Mike Hood ’67 was an advisor to ARVN Rangers during his second tour and was one of the last Americans in Quang Tri in 1972 when it was evacuated under fire. One of the last messages he received from his headquarters was “get to the citadel and we’ll try to get you out.”

In 1965, under the Johnson administration, the presence of U.S. combat troops in Vietnam increased, topping out at 543,000 in April 1969 (by comparison, U.S. troop strength in Iraq peaked at 168,000 and in Afghanistan at 110,000). During the height of the American War in Vietnam, U.S. units sought to engage the North Vietnamese Army (NVA or PAVN People’s Army of Vietnam) in large battles which favored American strengths in mobility and firepower. Any understanding of the Vietnam War would be incomplete without studying examples of the various branches of service within the Army.

Steve Darrah ’65 served two tours as an attack helicopter pilot. On one mission, his Cobra was providing support to a Huey that was trying to extract a Ranger team under heavy fire. Having expended his ammunition, Darrah volunteered to fly one more pass over the NVA guns while the Huey made a final attempt to rescue the Rangers. Darrah flew low and slow over the enemy with his searchlight on to draw fire, and the Huey was able to extract the Rangers. Russ Campbell ’65 served as an artillery forward observer and battery commander during his time in Vietnam. He highlights an especially poignant moment when, as a battery commander, he was faced with the decision of whether to fire into a “No-Fire Zone” at the request of an American lieutenant serving with the ARVN. Unsure of whether the lieutenant was engaged with the enemy or with another friendly force in the dark, Campbell “took a deep breath, looked at the fire direction center guys, and said, ‘fire’ and I just hoped.” The lieutenant replied, “Thank God, thank God,” and began directing the fire.

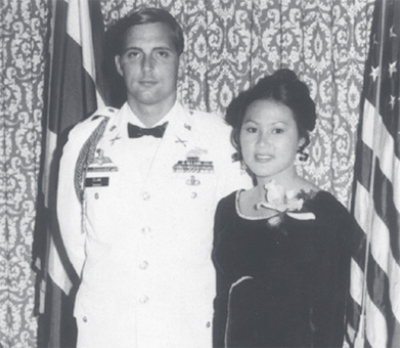

No story of the Vietnam War would be complete without the Vietnamese perspective. Mike Eiland ’61 was serving with Special Forces in Vietnam when he met Chan in Saigon, and they began courting. When Mike was transferred to a Special Forces detachment in Thailand, they agreed to marry if they could not stand being apart. In December they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. Nguyen Duc Huy was a Vietnamese nurse. He became especially close to an American civilian doctor, Pat Reardon, who was godfather to one of Mr. Huy’s children. As the war became increasingly desperate for South Vietnam, Mr. Huy offered to let Dr. Reardon adopt his godson to give him the opportunity for a good life in America. Dr. Reardon’s adopted son, Patrick Reardon, graduated from West Point in 1986 and eventually returned to Vietnam as the senior defense official in Hanoi. As he was leaving Vietnam for America in April 1975, Huy Duc Nguyen gave his son a bracelet etched with the Vietnamese words for “work hard, be happy, be obedient.” Those words motivated him, setting him on the path to West Point.

Cadets of the era were well aware of what was happening in Vietnam. The Pointer, the cadet magazine, regularly posted articles about the situation in Vietnam (five in 1967 alone), and Vietnam grad deaths were announced from the Poop Deck during lunch. One Catholic chaplain, Cardinal O’Brien, was so moved by the number of funerals at West Point that he volunteered for service in Vietnam. Rich Enners ’71 remembers the day in 1968 when his tactical officer came to his room to tell him that his older brother Ray (USMA ’67) had been killed in Vietnam. Rich visited his brother’s grave daily in the West Point Cemetery, and Ray, a three-year letter winner for the Army lacrosse program and a 1967 U.S. Intercollegiate Lacrosse Association Honorable Mention All-American, is memorialized in the naming of the Foley, Enners, Nathe Lacrosse Center, which opened in 2016.

In addition to seeing protests about the Vietnam War, cadets experienced the growing Civil Rights movement. Art Hester ’65 struggled with the decision to remain at West Point while demonstrations were increasing around the country, ultimately choosing to stay at West Point. After graduation, he deployed to Vietnam with the 101st Airborne Division, serving 34 years in the Army. Several West Point graduates deployed to places around the United States in the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968.

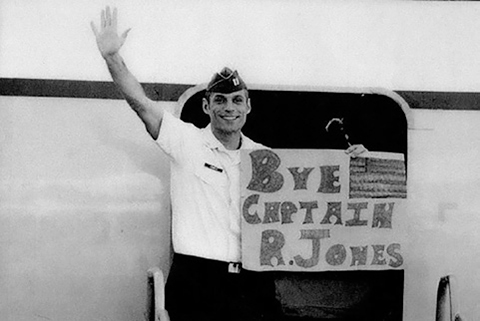

Throughout the war, hundreds of Americans were held prisoner by the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. The majority were pilots from all services who were shot down or forced to eject. Gene Deatrick ’46 (USAF) spotted escaped POW Dieter Dengler from his airplane, facilitating his rescue. Bob Jones ’65 was captured after ejecting from his damaged F-4 Phantom, enduring more than five years in the “Hanoi Hilton.” Describing his experiences in prison, he recalls, “Someone’s in the room and screaming, and all of a sudden you realize it’s you.” He was finally released on March 14, 1973, noting, “That was a pretty good day.”

Throughout the war, families of deployed service members suffered as well. They dealt with forced relocation from military bases (family members were not allowed to remain on post when their spouses were deployed), protests, and death notices. Susie Rothmann (wife of Harry Rothmann ’67) describes driving to Washington, DC to support Eileen Kelly after her husband, John “Jack” Kelly, was killed in action. Kitsy Van Deusen Westmoreland grew up in an Army family and married William Westmoreland ’36. She describes her experiences as an Army spouse, including being the Superintendent’s wife, living in Vietnam, and serving on Red Cross flights bringing wounded service members home. Stories from the home front help complete the larger narrative of the Vietnam War.

After the war, veterans sought to come to grips with their experiences, and a movement to establish a national monument gained momentum. Joe Zengerle ’64 was serving as an assistant secretary of the Air Force and was working with Jan Scruggs on the idea for a monument. Zengerle provided hangar space for the architects to display their designs. After Maya Lin’s was selected, opponents sought to prevent the monument from being built. Tom Shull ’73, serving as a White House Fellow, was instrumental in securing the building permits at the last minute, allowing construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (dedicated in 1982) to begin.

The Vietnam War was a central experience in the careers of many West Point graduates from the 1950s and 1960s. It affected the lives of cadets, graduates, and their family members. Casualties from the Vietnam War rest in long rows in the West Point Cemetery and are memorialized on individual plaques in Cullum Hall. A tablet affixed to a rock next to Lusk Reservoir honors the classes of the 1960s and those who “fell in battle in the Vietnam conflict.” Their stories of service and sacrifice continue to educate and inspire cadets today as the Long Gray Line continues.

LTC (R) David Siry is the Director of the West Point Center for Oral History (COH) and an instructor in the Department of History. A 1994 graduate of West Point, he served 28 years on active duty. Full-length interviews with all the individuals mentioned in the article are available online at www.westpointcoh.org. Currently, COH has 834 interviews published online, with 361 of them pertaining to the war in Vietnam. Its online holdings even include a feature-length film documenting the experience of the Class of 1967 before, during, and after their service in Vietnam. COH’s Vietnam Archive (sponsored through Margin of Excellence funding from the West Point Class of 1965) provides a broad lens through which to view the war in Vietnam.