By SSG Briana Hoffman, Guest Author

In 1816, a young Irishman set sail across the Atlantic toward the promise of a new job and a better life in America, beginning a journey that would change the course of not only West Point, but the entirety of American music history.

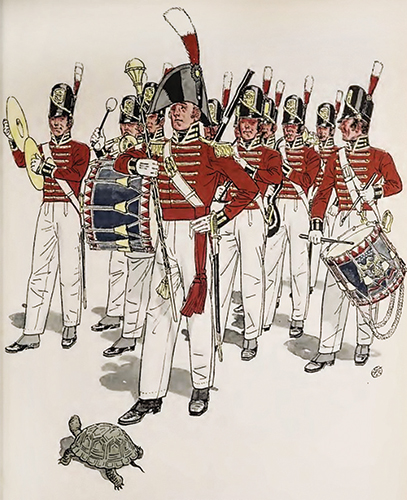

Richard Willis came to renown in his native Dublin as the first virtuoso of a newly invented instrument, the Kent (or keyed) bugle. The importance of this invention cannot be overstated as it allowed the bugle, formerly confined to a modest selection of disparate pitches, the capability to sound all notes of the chromatic scale, opening the door to an entirely new world of music-making for its practitioners.

While Willis’ career sky-rocketed in Ireland, on the other side of the ocean, American military music faced a day of reckoning.

During the American Revolution, soldiers expressed the desire for an improved class of military musician. In 1777, General George Washington experienced the music of the Army and bluntly described it as “very bad.”

However, as Washington noted in the same missive, “Nothing is more agreeable, and ornamental, than good music.” He directed that “every officer, for the credit of his corps, should take care to provide it,” while ordering musicians to improve post-haste or risk demotion.

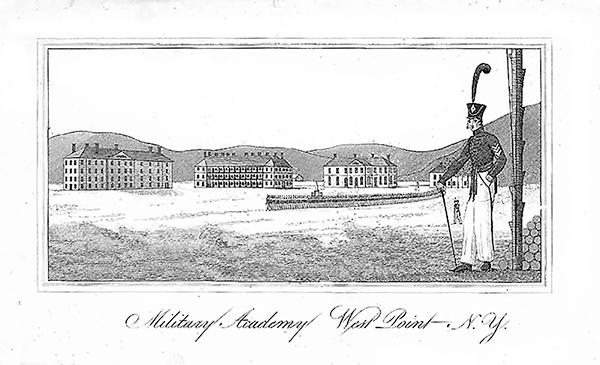

West Point joined with the rest of the Army in bettering the service’s musical situation, making incremental steps to sharpen the skill of its field musicians and provide more opportunities for cadets to learn (and be entertained by) music and dance.

When the need for a full-time Teacher of Music became apparent—or, as then Superintendent Joseph G. Swift, Class of 1802, ordered, “furnish more Band”—the first name that came up was that of the world-famous Willis. In 1816, he accepted the job as the Academy’s Teacher of Music.

Though musicians had been present since the first militiamen set foot on West Point, the arrival of Willis and the formal establishment of the West Point Band in 1817 represented a departure from the Academy’s previous utilitarian usage of its musicians. As noted by Brevet Brigadier General Sylvanus Thayer, Class of 1808, in the memoirs of his time as West Point Superintendent, for the first time, musical affairs took a place of distinction at the Academy. This new prominence allowed cadets the opportunity to learn and express themselves through music. Even plebes were permitted to keep and play their own instruments and, if interested, to avail themselves of the musical lessons provided by the Teacher of Music.

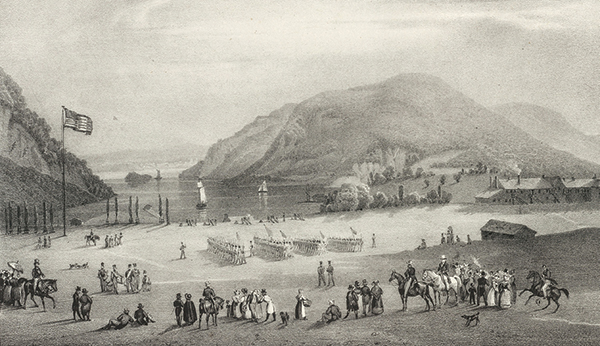

By 1823, the “very bad” Army music described by Washington was a thing of the past at West Point. One observer, author Eliza Leslie, called the West Point Band “the finest military band in America” and described its performances as “far superior to any of the concerts in Philadelphia or New York.” In 1827, a cadet who was admitted to the United States Military Academy in July of that year echoed those sentiments, writing to a friend, “We have the best band of musick [sic] in the United States, which keeps a fellow’s spirits up.” During this time, the band’s renown and Willis’ fame began to draw large crowds to West Point, representing one of the Academy’s first public affairs ventures.

While the West Point Band maintained its traditional duties—sounding the calls that regulated the duty day, keeping cadets in step on parade (which at that time occurred twice daily), playing sacred music in camp, and performing honors for funerals and other military ceremonies—Willis massively increased the band’s entertainment endeavors, both in frequency and in skill level. Under Willis’ leadership, the band began to host public performances multiple times a week on the Plain and in the large hall at West Point, at regular engagements in New York City and Philadelphia, and as featured entertainment for distinguished guests of the Academy, most notably the Marquis de Lafayette in 1824. Willis also began the tradition of musical celebrations in observance of Independence Day at West Point, with the Post’s first Fourth of July concert taking place al fresco at Fort Putnam.

In another of Willis’ lasting innovations at West Point, the band often performed atop the Plain at West Point, and vessels on the Hudson River, many of which carried “the most respectable people of Newburgh and Poughkeepsie on their way to New York,” would drop anchor and remain for hours listening to the West Point Band and “the divine echo of [Willis’] bugle from the mountains.” Today, the West Point Band continues Willis’ tradition with its annual summer concerts at Trophy Point, overlooking the Hudson River.

Willis’ compositional legacy lives on in his beloved songs inspired by life at West Point. Chief among these is “The Dashing White Sergeant,” which is still performed today and featured in the West Point Graduation March.

He also played a key role in the development of one of America’s most influential musical figures, Francis Johnson. In fact, Johnson held Willis in such esteem that one of his most famous compositions, a tribute called “The Death of Willis,” begins with an inscription stating: Music composed by Francis Johnson, musician of Philadelphia, as a tribute of respect to [Willis’] memory for the unusual and kind attention to him in forwarding in him a knowledge of that fine and martial instrument, the Kent bugle, when first introduced into this country.

Johnson is best known today as the first African American to have his music published, the first to perform in integrated concerts with white musicians, and likely the first American of any race to take his band overseas to Europe. Due to the circumstances of the time, Johnson was also one of the few teachers and employers of black musicians, allowing his peers access and opportunity to hone their musical skills. This cultural tipping point laid the groundwork for black musicians at the turn of the century to develop America’s first original musical genre: jazz.

When Willis passed away in 1830, his impact on the Corps of Cadets was evident at his funeral, which was attended by more than 200 of the 221 cadets enrolled at the Academy at that time. One cadet who participated in the funeral, Daniel P. Whiting, Class of 1832, described the death of “our justly celebrated musician” as a great loss for all those “who have once heard his soul-inspiring bugle and hoped to listen to it again.” Willis was laid to rest in a “humble spot” at the West Point Cemetery (the exact location has been lost to the annals of history) as the West Point Band marched the funerary procession that Willis himself had so often performed throughout his service.

Originally from Portland, Oregon, SSG Briana Hoffman has served as principal bassoon of the West Point Band since 2013. She holds dual bachelor’s degrees from Rice University and a graduate diploma from Oberlin College.

Read the complete Spring 2023 edition of West Point magazine here.