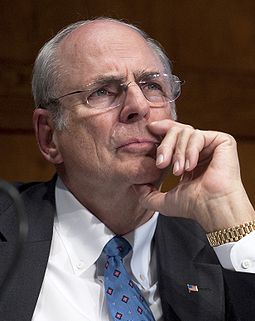

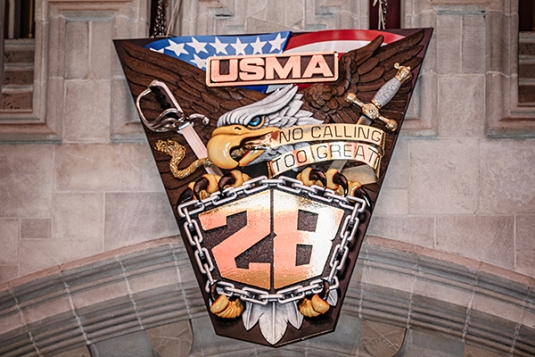

As a distinguished public servant and leader of industry, Norman R. Augustine has rendered a lifetime of outstanding service to the United States and its citizens. In government service and in multiple fields of aerospace engineering and industrial production, he has exemplified the ideals of West Point, as expressed in its motto, “Duty, Honor, Country.”

As a public servant, first in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and, later, at the highest levels of the Department of the Army, Mr. Augustine helped revitalize the post–Viet Nam Army and led the development and fielding of the M-1 Abrams main battle tank, the Bradley Infantry fighting vehicle, the Patriot air defense system, and the Apache attack helicopter. His efforts in the 1970s ensured the materiel excellence of the Army that routed Iraqi forces during Operation Desert Storm.

Upon leaving the Pentagon in 1977, Mr. Augustine joined Martin Marietta as vice president for Aerospace Technical Operations. Within a decade, he rose to become president of the corporation’s Denver Aerospace unit, the organization that produced Titan missiles and external fuel tanks for the Space Shuttle. In 1986, he became Denver Aerospace’s president and CEO and, two years later, its chairman and CEO, assuming corporate leadership just as the Cold War ended and the era of downsizing the military establishment began. Adapting to this new paradigm, he diversified corporate operations and commenced an aggressive campaign of acquisitions and mergers. The most significant of these was the merger with Lockheed that produced the new defense contracting giant, Lockheed Martin. This corporate creation of Norman Augustine has produced marked gains in efficiency, productivity, and cost savings in the development and fielding of equipment and materiel for the Armed Services.

Norman Augustine retired from active corporate leadership in 1997, staying on as the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Board. He then ventured into the field of higher education, joining the faculty of the Princeton University School of Engineering and Applied Science.

During his spectacular rise to corporate prominence, Mr. Augustine also continued serving the nation through public service, chairing numerous White House, Senatorial, Department of Defense, Army, Air Force, Treasury, Energy, and NASA advisory boards and committees. Additionally, he chaired or served on an even greater number of public service and aerospace industry panels and organizations. He is the former president of the Boy Scouts of America, former national chairman of the U.S. Savings Bond Campaign, former chairman of the National Academy of Engineering, the chairman of the Council of Trustees of the Association of the United States Army, and for the past seven years, Chairman of the American Red Cross.

Norman Augustine’s more than seventy-five governmental, civil, academic, and industry awards and citations certify his lifetime of accomplishment. He is the recipient of the nation’s highest technological achievement award, the National Medal of Technology. He has been cited five times with the Defense Department’s highest civilian decoration, the Distinguished Service Medal. He is the recipient of similar awards from the Departments of the Army, Air Force, Treasury, Transportation, Energy, NASA, and NATO.

In 1998, the Association of the United States Army awarded Norman Augustine its highest honor, the George Catlett Marshall Medal. He has been cited by the Library of Congress as one of “Fifty Great Americans.”

Norman Augustine has given selflessly of his time, energy, and enormous talent to the national community. His extraordinary contributions to the aerospace industry, to higher education, to the United States Space Program, to national security, and to his fellow citizens symbolize and reflect the principles and ideals of West Point. Accordingly, the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy hereby presents the 1999 Sylvanus Thayer Award to Norman R. Augustine.

Speech

Remarks by Norman R. Augustine

Retired Chairman of Lockheed Martin Corporation

Upon receiving the West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award

United States Military Academy

15 Sep 1999

When a dear friend of mine, a former senior government official, learned of this occasion, he sent me a letter in which he stated unequivocally that there is no recognition more significant than the Thayer Award. I agree wholeheartedly, given the award’s association with the United States Military Academy. There is no other institution in the entire world — none — that can point to so distinguished a group of graduates.

That said, Chairman Hammack’s extremely generous introduction does, however, remind me of the time another friend of mine, David Roderick, then CEO of U.S. Steel Corporation, was introduced to an audience as one of America’s greatest businesspersons. As proof, the moderator said simply that David had made a million dollars in California oil. It was evident, as David approached the podium, that he was somewhat embarrassed, and he began his remarks by pointing out that although the introduction was “essentially” correct, it had not been California, it was Pennsylvania . . . it wasn’t oil, it was coal . . . it wasn’t a million dollars, it was ten thousand . . . and it was not he, it was his brother. And he didn’t make it, he lost it!

Chairman Hammack’s remarks also call to mind an incident that occurred a number of years ago, just after I completed my service as Under Secretary of the Army. I was speaking with the then–newly announced Chief of Staff about his challenging assignment, and I asked him how he felt taking a job once held by the likes of Marshall, Eisenhower, MacArthur, and Pershing. I don’t remember his exact response, but I did receive a letter from him a few weeks ago concerning this evening’s award, and he was kind enough not to ask me how it feels to speak from essentially the same platform where GEN MacArthur accepted the Thayer Award and presented one of the most stirring speeches in American history.

In short, I know of no words equal to the occasion except for a simple, heartfelt “thank you.”

My only regret is that my Dad could not be here to witness these festivities. Corporal Ralph H. Augustine, Company “E,” 39th Infantry, was a doughboy who served in France and Germany during and after WWI. I will never forget the advice he gave me regarding occasions such as the one in which I find myself this evening. He said, “Son, when you see a frog on top of a flagpole, he didn’t get there by himself.”

As usual, Dad was right. I do owe a great deal to the many people who helped place me before you tonight. Above all, I am indebted to my wife and most faithful friend, Meg.

A few days ago—anticipating that I might find myself at a loss for words this evening—I asked Meg if she had any thoughts about what remarks I might offer. Her advice was typically straightforward and wise: “Well,” she said, “whatever you do, don’t try to sound intellectual or witty or charming—just be yourself.”

And that is what I mean to do. You see, for nearly 40 years I have had the privilege of observing the men and women of the United States Army firsthand—with my own eyes. I have watched America’s soldiers from an office in the Marshall Corridor in the Pentagon to the loneliest outposts near Panmunjom along the DMZ in Korea—from Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin to An Loc in Viet Nam—from the Fulda Gap in Germany to a hundred other troubled places around the globe where American soldiers have stood guard to help assure the freedom of America and its allies.

I could not accept this award without a word of gratitude to them, their predecessors, and those, like you, who will join them. And as much as I treasure the significance of this evening’s recognition, you should know that I take equal pride in having been made an Honorary Command Sergeant Major in the United States Army.

My view of America’s soldiers was solidified early in my second Pentagon tour when, as Under Secretary, I set out to visit every division in the active Army and a number of units in the Reserve components—wherever in the world they might be—all within my first 100 days in office. At the end of that tour, I returned to the Pentagon filled with even greater pride in America’s soldiers—for their professionalism, courage, sacrifice, selflessness, and, above all, their devotion to country.

In the course of that tour, I encountered hundreds, even thousands, of soldiers, one who held two PhDs and a whole handful of Purple Hearts; another, a medic who had removed a live grenade lodged in a soldier’s back; still another who had survived no fewer than seven helicopter crashes. He confided, “They should have loaned me to the enemy.”

There are dozens of vignettes that I could share with you this evening—little incidents that for me shed light on what historian John Keegan must have meant when he wrote that “soldiers are not as other men.”

On the other hand, whether the soldiers I encountered were equally enchanted with this occasional visitor from the labyrinthine maze of Washington is quite another story.

I recall a trip to Okinawa during a time that I was Acting Secretary of the Army. I was introduced to a group of GIs by their sergeant major, who enthusiastically informed the soldiers that “the Secretary,” as he referred to me, was there to observe their training—but time would be short. In the sergeant major’s words, “ ‘The Secretary’ will tour the barracks. Then ‘the Secretary’ will attend a luncheon in his honor hosted by local dignitaries. After a television interview, ‘the Secretary’ will fly on to Thailand to meet with that nation’s military leaders.”

An even more deflating incident occurred some years earlier when I arrived from my office in the Pentagon for an inspection tour in Viet Nam—a few weeks before the Tet Offensive. We landed in-country at midnight, and, as I was transferring in the darkness to a helicopter, I was presented with a flak jacket and instructed rather unceremoniously, “Use it.”

Being the lone civilian among soldiers, and, worse yet, at that time being a representative of the Office of the Secretary of Defense—which, in those days, was only slightly less popular than the Viet Cong—and feeling particularly conspicuous in the khakis I had been issued, which bore no insignia anywhere yet raised suspicion everywhere of some surreptitious connection with the CIA—I dutifully put on my flak jacket.

Once we were airborne, I noticed that no one else was wearing one. As the stifling heat began to wear on me, I leaned over and asked the officer seated next to me in the helicopter why I was the only one who had to wear a flak jacket. No sooner had the words left my mouth then the geometry of the circumstance sunk in. Speaking with a hint of bemusement, the officer patiently explained over the intercom for all to hear: “In a helicopter, Sir, you’re supposed to sit on it!”

Minor embarrassments aside, my association with our Army has assured me that the American people can rest secure in the knowledge that their Army will never fail them, because if it ever did—as GEN MacArthur pledged in this very hall when receiving this same award 37 years ago—a million ghosts would rise from their rest, intoning the words by which the Corps of Cadets still lives: “Duty, Honor, Country.”

What is it that has caused me to choose to spend so much of my life in the company of America’s soldiers? Part of the answer was put into words by a grizzled old paratrooper I met on a visit to the 82d Airborne Division at Ft. Bragg. Someone in our group asked the soldier how many times he had jumped from an airplane. I don’t recall his precise answer—and he did have a precise answer—but I remember that it was well over a thousand.

Now, I must confess that as an aeronautical engineer, I have never entirely understood the principle of jumping out of perfectly good airplanes. Reflecting our general astonishment, one of our group remarked, “You sure must like to jump.” To which the soldier replied, “No, I hate to jump.” The puzzled questioner pressed the matter: “You’re in a volunteer Army, in a volunteer outfit. Why do you jump?” Without hesitation, the soldier explained, “Because I like to be around the kind of people who do.” And like that grizzled Airborne soldier, I like being around the kind of people who choose to serve our nation in its Army.

I don’t need to tell you that serving in America’s Army is not an easy calling. The perils are many, the separations from loved ones frequent. By one count in the last 10 years alone, U.S. troops have been deployed 34 times in response to international crises—and the horizon appears little different. And, yes, all too often our soldiers are taken for granted by the very people they are asked to protect—including some of those right here at home.

But in a world with seemingly few heroes, America’s soldiers stand out. You are the embodiment of a hallowed code of honor.

There is a story told about one of your distinguished predecessors, whose portrait hangs in this room. Near the end of his life, when he served as president of what is now Washington & Lee University, Robert E. Lee was approached by a woman with a small boy in her arms. She asked the old general what advice he would have for her son. Lee thought for a moment and then answered simply, “Teach him to deny himself.” To be such a man or woman, selfless and dedicated to mission, is a noble aspiration. To lead such men and women, as you soon will, is one of the greatest honors—and greatest responsibilities—that can be bestowed in American life. One warrior who lies buried a short walk from here, George Armstrong Custer, said it well: “The reward of command is the opportunity to lead, not to have a bigger tent.”

I expect that is why West Point remains among the most admired and cherished institutions in all America. It is truly a national asset. Why do I say that? I mentioned four good reasons already: Lee, Pershing, Eisenhower, and MacArthur. Want more? How about Bradley, Stilwell, Taylor, Ridgway, Abrams, and McAuliffe? Or try Grant, Patton, Schwarzkopf, and Borman. And I haven’t even mentioned Davis, Blanchard, Dawkins, Doubleday, or Coach “K”—or, for that matter, your predecessors who went on to distinguish themselves in areas far removed from either playing fields or battlefields, Americans like Goethals, Poe, and Whistler.

These and the thousands of other West Point alumni who have served our country with distinction in a whole variety of fields have won for this Academy a special place in the hearts of all Americans.

Consider a recent survey—it indicated a serious and troublesome disconnect between most Americans and many of the institutions that make up American life. For example, only 21% of the respondents said they had a great deal of confidence in the federal government. On the other hand, 59% expressed a great deal of confidence in America’s military — a confidence level, incidentally, far eclipsing business, Congress, or the news media.

As you endure the daily rigors of cadet life, receiving your quarter-million-dollar education—in whatever fashion it is dispensed—it may be difficult for you to fully appreciate the esteem with which your countrymen regard you. They know that the Long Gray Line is there; that the demands placed on you and the devotion with which you must meet your responsibilities go far beyond those of any business executive, TV personality, or almost any politician.

In the War for Independence, GEN George Washington said he considered West Point “the most important post in America.” The passage of more than two centuries has shown that he was right in ways he couldn’t even imagine.

Take the all-important matter of leadership. The list of accomplishments of your predecessors is convincing evidence of the Academy’s success in teaching leadership skills. No one does it better. The annals of military history as well as the civilian affairs of our nation are replete with testimony to this fact.

Let me mention a few examples of how the same qualities of leadership taught at West Point have had a profound impact in some of the pursuits to which I have devoted much of my life.

During my tenure as CEO of Martin Marietta Corporation, we worked intensely in partnership with the Lockheed Corporation for nearly a year on a project that was extremely important to our two companies. One day, an opportunity arose which would assure the success of our endeavor. What was proposed was perfectly legal, but somehow it didn’t seem right.

I telephoned Lockheed’s CEO, Dan Tellep. Our partner’s response was immediate and matched my own intuition: “Let’s not do it,” he said. The short-term consequence was that our project failed, but the long-term consequence was that the trust that developed between the two companies was the major factor in bringing about the eventual merger of these organizations to create the world’s largest defense firm.

Turning to another of my loves, during my years with the American Red Cross I was once asked by a business associate, a vice president of Lockheed Martin, who was about to retire, what I thought he should do with his free time. As you might suspect, I impartially suggested he become a Red Cross volunteer! A year or so later I received a water-stained envelope from him containing a letter which began, “I have spent the entire day standing up to my waist in flood waters handing out rolls of toilet paper.” He went on to say, “For some reason I thought of you!” But he closed with the words, “It was the finest day of my life.”

Then there were the trips I took to the North and South Poles. The former was sponsored by the Explorers Club and included my son, Greg, a Texas Aggie, and also a West Point graduate by the name of Buzz Aldrin. While at the other end of the earth, in Antarctica, I had the opportunity to enter the hut that remains as a silent monument to Sir Ernest Shackleton and his incredible journeys to that continent. The most extraordinary of those adventures began in 1915 with a daunting ad in the Times of London, that read: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honor and recognition in case of success.”

There is something about great challenges that brings out great leadership. In the business world, my predecessor as CEO of Martin Marietta, Tom Pownall, was called upon to lead our company against a hostile takeover attempt by another firm—the business world’s equivalent of a nuclear strike.

Having attacked first, our antagonist was able to buy a majority of the stock in our company before we could react. They thus owned us lock, stock, and barrel. Our prospects were somewhere between bleak and nonexistent. Undaunted, Pownall, in a display of incredible leadership audacity, quickly went out and purchased a majority of the other company’s stock. We thus literally owned each other—a situation that gave us the leverage we needed to eventually escape with our independence. In the end, it was our antagonist who ceased to exist while our firm went on to prosper.

Pownall, it should perhaps be noted, was a graduate of the academy of a sister service. Some years later, I happened to see a letter that this respected and remarkably successful business executive had written to a military officer who was considering leaving the service. Pownall wrote that his own decision to leave the military was the greatest mistake he had made in his entire life.

Turning to my own profession—engineering—there is the story of a friend by the name of Bill LeMessurier. To his great dismay, he one day discovered a design flaw in a New York City skyscraper that had just been built under his supervision—a flaw that could potentially cause the building to collapse. No one knew about this hidden timebomb but LeMessurier himself. What to do?

He promptly reported the matter to the building’s owners and to city government officials. After a few troubled months, it turned out that the building could be strengthened and saved.

While I was working in the Pentagon some years ago in the research and development area, one dismal day we discovered that, through some inexplicable error, the Army’s Blackhawk helicopter, then about to begin flight testing, had been misdesigned. The error was not profound; it was embarrassingly simple: The helicopter was two inches too high to fit inside the Air Force transport aircraft that was supposed to deliver it to the theater of combat. A debate quickly broke out among some of the civilians present about whether we should inform the Congress—which at that very time was considering canceling the project—or whether we should attempt to quickly and quietly find a fix.

The argument was abruptly settled when Secretary of the Army and West Point graduate Bo Calloway simply picked up the telephone and called the heads of the four responsible Congressional committees and leveled with them. I am convinced that Calloway’s forthrightness was a major reason Congress eventually supported the Blackhawk which, as you know, has gone on to be a great success.

These are just a few of dozens of examples with which I am familiar from my own fields of interest—examples that underscore the importance of the very attributes cherished at West Point: integrity, courage, service, perseverance, self-discipline, and honesty.

A few weeks ago, my much-admired friend, Ken Adelman, and I completed our most recent effort in collaborative writing, a business book originally titled Shakespeare on Management. But before we could complete the manuscript, our publisher, Miramax, also in the movie business, released the hit, Shakespeare in Love. This caused them to change the title of our book to Shakespeare in Charge!

The opening chapter, not surprisingly, deals with leadership. In it, we focus on Henry V and the Battle of Agincourt. As I’m sure you recall in that famous scene before the fateful engagement, King Henry sees that his troops are tired, demoralized, and unmotivated. They are outnumbered five to one and fighting on the other guy’s turf. With staves and arrows, they face the mounted knights of France in all their glory.

Ignoring the odds, Henry appeals to his army just as the battle is about to begin. His stirring speech echoes through the ages, culminating in the immortal lines that I am sure have special meaning to all who walk these hallowed halls, men and women alike:

“From this day to the ending of the world, But we in it shall be remembered; We few, we happy few, we band of brothers . . . . ” I have been greatly privileged to share your camaraderie as few civilians ever do, and I stand in admiration of this place and the people who make it what it is.

I would close by thanking you again for allowing me to share in your fellowship and in the great tradition of this institution. I wish each of you Godspeed as you serve our country.