“Receiving the Thayer Award makes me feel closer to West Point than I’ve ever felt before,” said General Ann Dunwoody (Retired), in an interview just prior to receiving the 62nd annual Sylvanus Thayer Award. A remarkable statement given that Dunwoody, the first woman in U.S. military history to achieve the rank of four-star general, comes from a four-generation legacy of West Point graduates: her father (Harold H. Dunwoody, Class of 1943), her grandfather (Halsey Dunwoody, Class of 1905), her great-grandfather (Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody, Class of 1866, and her brother, Harold “Buck” Dunwoody Jr. ’70). “I’ve been here a lot,” she joked.

Yet in addition to her long and strong West Point lineage, Dunwoody’s personal devotion to the values of “Duty, Honor, Country,” the central tenet of the Thayer Award, actually come from her 38 years of distinguished service to the country. “In my Army career, I’ve learned that ‘Duty Honor, Country’ is more than three words: It’s a way of life,” she says.

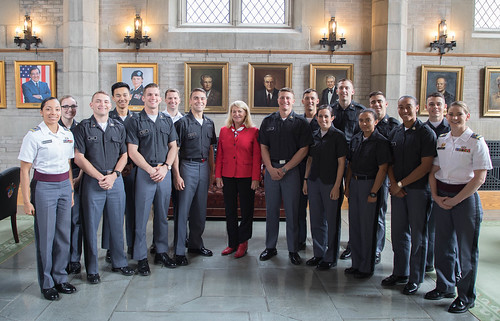

In 1974, Dunwoody joined the Women’s Army Corps during her junior year at the State University of New York College at Cortland when she learned it paid $500 a month, and planned to stay in long enough to fulfill her two-year commitment. “I joined for the money, but I stayed because I ended up loving being a soldier and leading soldiers,” Dunwoody told a group of 15 cadets from the Black and Gold Forum in an event before the Thayer Award ceremony. “I learned that the Army is a values-based organization, one that gives its people all the tools they need to make a difference, and I decided to stay in as long as I could make that difference.”

Upon her graduation from college, Dunwoody was commissioned as a second lieutenant with the Quartermaster Corps. Her first assignment was as a platoon leader with the 226th Maintenance Company, 100th Supply and Services Battalion at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, a company she later commanded. In her three-plus decades as a Quartermaster Corps officer, she achieved several notable “firsts,” including being the first woman to command a battalion in the 82nd Airborne Division; the first female general officer at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; and the first woman to command the Combined Arms Support Command at Fort Lee, Virginia. Dunwoody also deployed overseas for Operation Desert Shield/Operation Desert Storm and, as 1st Corps Support Command commander, deployed the Logistics Task Force in support of Operation Enduring Freedom I. Her major staff assignments included: Planner for the Chief of Staff of the Army; Executive Officer to the Director, Defense Logistics Agency; and Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics G-4. As commander of Surface Deployment and Distribution Command, Dunwoody supported the largest deployment and redeployment of U.S. forces since World War II.

In her last assignment, Dunwoody led and ran the Army Materiel Command, the largest global logistics command in the Army, comprising 69,000 soldiers and civilians located in all 50 states and more than 140 countries. She managed a budget of $60B and was responsible for the Army’s Research and Development, Installation and Contingency contracting, Foreign Military Sales, Security Assistance, Supply Chain Management, all Army Depots supporting supply and maintenance functions, manufacturing sites and ammunition plants. Dunwoody led the transformation of the Army’s logistics organizations, processes and doctrine in support of an expeditionary Army. General Ray Odierno ’76 (Retired), the 38th Chief of Staff of the Army, once called Dunwoody “quite simply the best logistician the Army has ever had.”

“General Dunwoody is one of the Army’s most outstanding leaders,” said Superintendent Lieutenant General Darryl Williams ’83, the 60th Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, in his remarks introducing the 2019 Thayer Award recipient. “I can think of no better example of a leader of character or exemplar of our Army’s values and the West Point ideals of ‘Duty, Honor, Country’ than General Ann Dunwoody.”

After expressing her feelings of honor, humility, and gratitude in the introduction of her acceptance speech for the Thayer Award, Dunwoody transitioned to some of the leadership lessons she learned throughout her long Army career, most of which centered on “standards” (in 2013 she authored a book titled A Higher Standard—Leadership Strategies from America’s First Female Four-Star General). “When I joined the Army back in 1975, I just assumed that, as a woman, I’d have to exceed the standard to be accepted in the ranks,” she said. “But what I learned in my journey is that all the good leaders that I looked up to held themselves to a higher standard and encouraged their subordinates to do the same.”

Dunwoody had the opportunity to view the standard at West Point when she, like all Thayer Award recipients before her, trooped the line with the Superintendent during a review of the Corps of Cadets assembled in formation on the Plain in her honor. “You looked fantastic,” Dunwoody told the cadets during her speech, “and as I look out in the audience now, I see the faces of the future: I see the future leadership of our U.S. Army, an Army I’ve been around my entire life, an Army of opportunity, and an Army that I have always loved and will continue to love all the days I have left on this earth.”

“General Dunwoody’s leadership, love of country, and untiring efforts to make our nation better and stronger are lessons all Americans can admire,” said Lieutenant General Joseph DeFrancisco ’65 (Retired)EA, Chairman of the West Point Association of Graduates, before presenting Dunwoody with the Thayer Award. “I can say without hesitation that General Dunwoody’s name on West Point’s Thayer Award plaque greatly enriches the prestige of our alma mater.”

In the concluding moments of her acceptance speech, Dunwoody returned to the specialness of West Point and why it is, in a way, an alma mater to her as well. “I’ll always come back to West Point for the history, for the traditions, and for the great soldiers I’ve known who have walked the Plain,” she said. “But, most importantly, I’ll come back to maintain my special relationship with this special place on the Hudson that connects me to my family tradition and to the Army that I love.”

Announcement

April 23, 2019

West Point, NY: The West Point Association of Graduates is pleased to announce that General Ann Dunwoody (USA, Ret.)—the first woman in U.S. history to achieve the rank of four-star general—will receive the 2019 Sylvanus Thayer Award. The award will be presented on October 10, 2019 during ceremonies hosted by Lt. Gen. Darryl A. Williams, Class of 1983, 60th Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

West Point Association of Graduates Board Chairman Lt. Gen. (USA, Ret.) Joseph E. DeFrancisco, Class of 1965, said, “The West Point Association of Graduates is honored to present the Thayer Award to General Ann Dunwoody. Her distinguished career of service to our nation spans more than 37 years and includes command at every level from second lieutenant platoon leader in the Quartermaster Corps to commanding general of Army Materiel Command, the Army’s largest global logistics command. Along the way she was a role model and inspiration to thousands of men and women in uniform who watched her become America’s first woman four star general based on her leadership, talent and determination. General Dunwoody is an exemplary American leader of character, whose lifetime of service exemplifies the West Point values of ‘Duty, Honor, Country.’ She embodies the proud legacy of our Association’s highest award. Having General Dunwoody forever associated with West Point through the Thayer Award speaks directly to its purpose of recognizing a citizen of the United States, other than a West Point graduate, whose outstanding character, accomplishments, and stature draw wholesome comparison to the qualities for which West Point strives.”

“I thank the West Point Association of Graduates for this high honor,” said General Dunwoody. “With four generations of West Point graduates in my family; my brother, my Dad, my Grandfather and my great Grandfather, I am especially proud that I will have the privilege of trooping the line, and the opportunity to salute the men and women of the Corps of Cadets who will lead and inspire our future Army.”

Speech

West Point, NY

October 10, 2019

Good evening. Thank you. I wish I could begin to describe the incredible feelings of gratitude and humility that are absolutely consuming me at this very moment. I am so incredibly honored to be this year’s recipient of the Sylvanus Thayer Award.

Thank you Lieutenant General and Mrs. Williams for being such gracious hosts. And thank you General Williams for that kind and passionate introduction. I think you know more about me than I do.

I’m truly grateful to the West Point Association of Graduates for selecting me for this award, and I’m equally grateful to this Corps of Cadets for making our stay here memorable and today’s ceremony so very special. I can assure you, I am standing here in total disbelief and awe.

I’m so honored to be joining a list of such distinguished awardees that includes four presidents, eight secretaries of state, four secretaries of defense, eight stalwarts of Congress, and seven general officers, as well as industrialists, diplomats, an astronaut and several just really great citizens, like Ross Perot and Gary Sinese. And, of course, one of my husband’s personal, all-time favorites…comedy legend Bob Hope! Believe me: that’s a pretty impressive group for a simple “foot-soldier” to be joining.

Back in 2008, at my promotion ceremony, with General George Casey officiating, we were in a large auditorium in the Pentagon, surrounded by an overflow crowd of family, friends and well-wishers; I knew I was facing one of the most difficult and emotionally charged speeches of my life.

Well, this evening’s festivities certainly rival those feelings, as I look out and see members of my family, friends, former bosses, as well as well-wishers, once again. I am so grateful to all of my family, a family full of patriots and selfless servants, for being here tonight. I know how busy you are, and I know how far you traveled to be here. Thank you for your continued love and support.

What’s even more exciting, as I look out at the audience, is that I see the faces of the future. I see the future leadership of our United States Army: an Army that I have been around my entire life, an Army that provided me opportunities, and an Army that I have always loved and will continue to love for all of the days that I have left on this earth.

During my career, I was blessed to achieve many military firsts in this Army. But what I want every one of you to know is that not one single day of my service did I ever consider myself a female soldier. Like most of you, I just considered myself a proud American soldier.

And for me, this day and this place have a very personal meaning. Today brings to life a story about a remarkable soldier, a soldier who is very special to me. This soldier was a young Armor officer who graduated from West Point in June 1943. Not long after his graduation, this young soldier found himself on the battlefields of Europe toward the end of World War II, serving in the 14th Armor Division, leading a group of equally young soldiers fighting along the French-German border in January 1945. This soldier was severely wounded in action when the tank he was in was blown up. In fact, his injuries were so severe he almost lost his leg. When the doctor told him he might have to amputate his leg, he responded, “Doctor, I’m going to keep this leg long enough to kick you in the ass with it.” Fortunately, he recovered and was awarded the Purple Heart.

Like so many of you here today, he was a true fighter—on the battlefield and off—and he continued to serve. In 1951 this soldier commanded the 3rd Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment in the Korean War. There, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for valor and received another Purple Heart…and he continued to serve. In 1971 this same soldier commanded the 5th Mechanized Brigade in Vietnam. This soldier was a proud three-war veteran, one of our greatest generation soldiers, and I’ll tell you there is no one more proud of him than me. That soldier’s name is Harold Halsey Dunwoody, my dad.

When people asked him about his two Purple Hearts, he was quick to say he was just a slow learner, but we all know better. I know much of my success is founded on what I learned from my dad, as a patriot and as a soldier. While my dad was a West Point grad, Class of ’43, his dad, Halsey, was West Point Class of 1905. And his granddad, Henry, graduated from the Point in 1866. My brother Buck, or Bucky as his classmates called him, was West Point Class of ’70. Now you understand why people think I have olive-drab blood running through my veins.

My brother Buck made a career in the business world after his service in the Army. I think he was surprised how well this education, this institution, and these traditions prepared him for a successful career outside the Army. Sadly, he passed away last year, way too young, way too early.

So while the long gray Dunwoody line is not physically here tonight, I know they are here in spirit. (And knowing my brother, he may still be walking hours on the Area in heaven.) I also know my mom is with us in spirit. My mom, a devout Catholic, was the strongest, most selfless, gracious, caring and loving person I have ever met. She pretty much raised six children on her own while dad was serving our nation. She taught us that the glass was always half full. And no matter where we were, no matter how tough the challenge, it was never going to rain on our parade. If there is anyone who deserves immediate entry into the order of sainthood, it is my mother, and I know she is smiling, just because this event created another opportunity for a Dunwoody family get-together.

Now, I could stand here and tell you that I always knew I wanted to be a soldier, but an Army career is not exactly how I envisioned my life unfolding. As far back as I can remember, I knew all I ever wanted to do was to coach and teach physical education. I competed in sports my entire life. This was before Title IX, when there were no sport scholarships for women. We just played for the love of the game. But I can assure you, even back then, I learned as much from losing as I did from winning, and I learned about building a team and building confidence. While not on my master plan, I ended up joining the Army right out of college, getting a direct commission as a second lieutenant with a two-year commitment. Heck, I figured I could stand on my head for two years! But it was always clear to me that my Army experience was just going to be a brief, two-year detour on the way to my childhood dream of being a coach.

Well after my two-year stint was up, I remember telling my dad that I really loved being a soldier and that I loved leading soldiers and that I was going to stay in as long as I enjoyed what I was doing and could make a difference. And that’s exactly what I tried to do, one job at a time.

So, my initial two years turned into five, turned into 10, and—yes—eventually 38.

But what I realized is that I really did end up fulfilling my childhood dream: I just did it in a different profession and in a different classroom. I ended up coaching thousands of young men and women on and off the battlefield in a very physically demanding profession, our United States Army.

So, when people ask me: Ann, did you ever think you were going to be a general officer, let alone a four-star? I tell them: Not in my wildest dreams! There was no one more surprised than me—except, of course, my husband. But, you all know what they say: “Behind every successful woman, there is an astonished man.”

My first assignment was Fort Sill, Oklahoma. There I met my very first platoon sergeant, Sergeant First Class Wendell Bowen, who was clearly the best non-commissioned officer in the company. I remember when they made the announcement that I was going to be Sergeant Bowen’s new platoon leader, Sergeant Bowen just looked at me, smiled, and with his Tennessee twang said, “Ma’am, I’m going to make you the best lieutenant in the United States Army.” Well, shortly after one of my typical second lieutenant blunders, I remember Sergeant Bowen shaking his head, smiling, and saying, “You are really going to make me work at this aren’t you ma’am?” But Sergeant Bowen took me under his wing and taught me how to be a good platoon leader. He was so good that the lessons he taught me in leadership not only permeated my leadership style but have stayed with me to this day.

One of the first and most important lessons he taught me was to never walk by a mistake. Think about that: never walk by a mistake. I was taught if you walk by a mistake, you just set a new lower standard. If you see a mistake, if you see someone doing something wrong and you turn the other way, then you just set a new, lower standard. And the new lower standard becomes the new standard in the eyes of the offender. By not making on-the-spot corrections, you send a message to your soldiers that standards aren’t important and that leaders are not responsible or accountable for policing the force. In the Army, a mistake can be something as minor as correcting a soldier who is shuffling down the sidewalk in uniform with his hands in his pockets, or something more significant like correcting a soldier who fails to properly clean and maintain his combat equipment. A poorly maintained weapon in training can result in a malfunction; a poorly maintained weapon in combat can be fatal. In the military failing to enforce standards can be a slippery slope that leads to poor performance, people getting hurt, or, even worse, an unnecessary loss of life.

One of my many great mentors and friends is General Dennis Reimer, our 33rd Army Chief of Staff. He used to talk passionately about values-based leadership. Now, if you say it real fast, it sounds easy and even common sense, but I can assure you that values-based, ethical leadership is neither easy nor common sense. If it were, we wouldn’t be subjected to the headlines we see about leaders with lapses in judgment, leaders who have failed to uphold the values and ethical conduct that sound so easy and so common sense.

When I joined the Army back in 1975, I just assumed, as a woman, I was going to have to prove myself and would have to exceed the standards in order to be accepted into the ranks. And I strove to do just that. But what I realized during my journey is that all the really good leaders I served with, all the good leaders I looked up to and respected, many of them sitting in the audience tonight, held themselves to a higher standard and encouraged their subordinates to do the same.

Growing up as an Army brat, I assumed my time in the Army was going to be personally and professionally rewarding; but, quite honestly, I never really thought about what my responsibilities were as a leader to safeguard the profession. And as I look back on my career, I now know the things we do as leaders will either help safeguard our profession or taint our profession in the eyes of the country we serve. And it’s important for you to know what I didn’t know: that what you do as a leader matters!

Your country, your classmates, and the soldiers you will lead in the future will expect that you will leave West Point with the moral and ethical skill sets to lead, decide, and motivate as you take your rightful place stewarding our profession of arms. At the end of the day, your success won’t be measured by the rank you achieved or how many parachute jumps you made or how fast you can run. Your lasting legacy will be the leadership you displayed 24/7, in and out of uniform, in peace and in war, doing the right thing for the right reason, doing what you know to be morally and ethically right.

Now I didn’t just skip down the yellow brick road in the land of Oz and wake up one morning and find myself a four-star general. There were obstacles, there were roadblocks, but there were also a lot of people willing to help. And I believe those obstacles and those roadblocks and those people willing to help exist in every profession and in any organization.

But if you believe in yourself, stay on the moral high ground, and never give up you will make believers out of non-believers. Try to be the best you can be and never let others dissuade you from something you are passionate about. Just think about it for a minute…if we let others unduly influence or make decisions for us, they win. If we let others drive us away from something we are passionate about or something we believe in, they win. Were there times when it would have been easy for me to run in the face of adversity? You bet! Were there times when I was afraid, angry, or frustrated? You bet! But at the end of the day, I would ask myself the question, “If I quit and take the easy road and don’t continue to try to make a difference, who is the real winner and who is the real loser?” And for me, the seemingly insurmountable challenges turned into opportunities.

It was all about leadership.

The thought I’d like to leave you with tonight is that most people, like yourselves, really do want to make a difference. And your country is counting on you to make that difference! The good leaders I know want to inspire and encourage people with strong, principled and ethical leadership. While the ideals of Duty, Honor and Country will long endure, it is the preparation that you do personally, physically, professionally and spiritually that will ensure you are truly prepared to live up to those high ideals.

When America needs a great general, an Eisenhower or a MacArthur, they will look first to those who have walked the Plain at West Point.

When America needs a secretary of state or defense, much as we have done today, they will look to those who are credentialed at West Point.

You are the future, and when called upon I know you will do your country, your fellow soldiers, your family and yourselves proud.

As for me, West Point will always be a special place. I’ll always come back for the history, traditions, and for the great soldiers I’ve known who have walked the Plain. But, most importantly, I’ll come back to maintain my special relationship with this special place on the Hudson that connects me to my family tradition and to the Army that I love!

As we sit in this wonderful hall this evening, thousands of our soldiers, sailors, airmen, marines, and coast guardsmen are deployed around the globe, in harm’s way, doing our nation’s heavy lifting. I know that you share my pride in our men and women in uniform and in their families. So, tonight, I’d like to accept this award on their behalf. Wherever they may be serving, please pray for their success and safe return. Thank you once again for this incredible honor!

God bless all of you! And God bless America!

Go Army, BEAT NAVY!

Biography

Ann E. Dunwoody was born at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where her father was serving as a career Army officer. She grew up in Germany and Belgium and graduated from Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe American High School. Despite coming from a four-generation Army family, Dunwoody always thought she’d be a physical education teacher and coach. This changed during her junior year at State University of New York College at Cortland when she attended a four-week Army introductory program, followed by an 11-week Women’s Officer Orientation Course. Upon graduation from SUNY Cortland with a degree in physical education, she was direct commissioned into the Women’s Army Corps.

Dunwoody’s first assignment was as a platoon leader with the 226th Maintenance Company, 100th Supply and Services Battalion at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, a company she later commanded. In her three-plus decades as a Quartermaster Corps officer, she achieved several notable “firsts,” including the first woman to command a battalion in the 82nd Airborne Division; the first female general officer at Fort Bragg, NC; and the first woman to command the Combined Arms Support Command at Fort Lee, Virginia. Dunwoody also deployed overseas for Operation Desert Shield/Operation Desert Storm and, as 1st Corps Support Command commander, deployed the Logistics Task Force in support of Operation Enduring Freedom I. Her major staff assignments include planner for the Chief of Staff of the Army; executive officer to the director, Defense Logistics Agency; and deputy chief of staff for Logistics G-4. As commander of Surface Deployment and Distribution Command, Dunwoody supported the largest deployment and redeployment of U.S. forces since World War II.

In her last assignment, Dunwoody led and ran Army Materiel Command, the largest global logistics command in the Army, comprising 69,000 soldiers and civilians located in all 50 states and more than 140 countries. She managed a budget of $60B and was responsible for the Army’s Research and Development, Installation and Contingency contracting, Foreign Military Sales, Security Assistance, Supply Chain Management, all Army Depots supporting supply and maintenance functions, manufacturing sites and ammunition plants. Dunwoody led the transformation of the Army’s logistics organizations, processes and doctrine in support of an expeditionary Army. General Ray Odierno (Retired), the 38th Chief of Staff of the Army, calls Dunwoody “quite simply the best logistician the Army has ever had.”

Dunwoody holds master’s degrees from the Florida Institute of Technology and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, and is a graduate of U.S. Army Airborne School and holds the Master Parachutist Badge. She has been decorated with the Army Distinguished Service Medal (2), the Defense Superior Service Medal, and the Legion of Merit (3). She has been recognized by the NCAA with its highest honor, the Theodore Roosevelt Award, by the Intercollegiate Tennis Association with its ITA Achievement Award, by France with its National Order of Merit, and in 2016, the Ellis Island Medal of Honor. She has been recognized by SUNY Cortland as a Distinguished Alumna, received the Jerome P. Keuper Distinguished Alumni Award from the Florida Institute of Technology, and in 2018 was inducted in the inaugural class of the 82nd Airborne Division Hall of Fame. In 2013, she authored the book A Higher Standard—Leadership Strategies from America’s First Female Four-Star General. Today General Dunwoody is president of First 2 Four, LLC, a leadership mentoring and strategic advisory services company and serves on a number of public, private and non-profit boards. Dunwoody’s great-grandfather, grandfather, and father were all graduates of the U.S. Military Academy: Brigadier General Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody (Retired), Class of 1866; Colonel Halsey Dunwoody (Retired), Class of 1905; and Brigadier General Harold H. Dunwoody (Retired), Class of 1943 June. Her brother, Harold H. “Buck” Dunwoody Jr., Class of 1970, was also a West Point graduate.