A distinguished educator, public servant, and author, the Honorable Henry Alfred Kissinger has rendered a lifetime of outstanding service to the United States. Through his extraordinary contributions to the nation and to the preservation of peace throughout the world, he has exemplified the ideals of West Point, as expressed in its motto, Duty, Honor, Country.

As an educator, Dr. Kissinger’s contributions to the study of 20th century political science, foreign policy, and international relations are without equal. Graduating summa cum laude from Harvard in 1950, he went on to earn his master’s and doctoral degrees in Government at that same institution. Then, in 1954, he joined the Harvard faculty, where he remained until 1969. During that time, he directed the Harvard International Studies Seminar, served with the Center for International Affairs, and directed the Defense Studies program. Upon concluding his tenure as Secretary of State in 1977, he returned to academe, joining the Georgetown University faculty as Professor of Diplomacy in the School of Foreign Service and counselor to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

As a public servant, Dr. Kissinger forged a reputation as the leading practitioner of the diplomatic art to emerge during the second half of the twentieth century. After President-elect Nixon appointed Dr. Kissinger his Assistant for National Security Affairs in 1968, he soon emerged as the President’s principal advisor and executive on foreign policy matters. His efforts to pursue the policy of “détente” with the Soviet Union led to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), and these eventually resulted in the SALT I Arms Agreement with the Soviet Union in 1972. He was the architect of the rapprochement policy between the United States and the People’s Republic of China in 1972. He played a crucial role in the implementation of President Nixon’s Vietnam policy, and after protracted negotiations, signed the peace agreement ending the United States’ armed involvement in the Vietnam War in 1973.

In September 1973, Dr. Kissinger was appointed Secretary of State, and in that office, he continued building his record of extraordinary achievements, including the “shuttle” diplomacy that effected the disengagement of opposing forces and established a truce among the belligerents in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. This led to disengagement agreements between Israel and Egypt and Syria in 1974. Dr. Kissinger continued as Secretary of State until President Ford left office.

After resuming his work as an educator, consultant, writer, and lecturer, Dr. Kissinger also continued to answer his nation’s call, as a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Board and as the leader of the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America.

As an author, Dr. Kissinger has contributed to the literature of political science, diplomacy, and international relations for more than five decades. His first book, A World Restored, published in 1957, is still regarded as seminal in the field of diplomatic history. His groundbreaking work Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy won the Woodrow Wilson Prize in 1958 and established him as a leading authority on U.S. strategic policy. His memoirs include The White House Years and Years of Upheaval on the Nixon years, and Years of Renewal on the Ford years. Dr. Kissinger also authored Diplomacy, a sweeping diplomatic history.

Dr. Kissinger’s honors abound: the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 (the nation’s highest civilian award), and the Medal of Liberty in 1986.

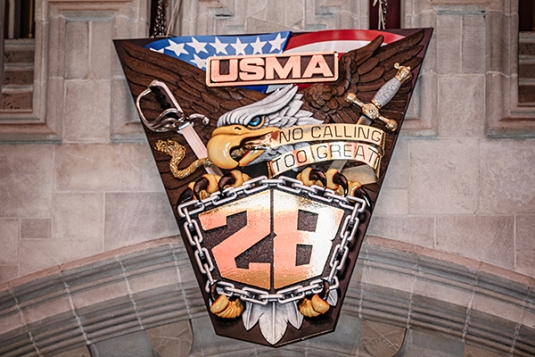

Dr. Kissinger has left an indelible mark upon the diplomatic history of the United States and the world family of nations. His matchless record of achievement manifests an uncommon dedication to the citizens of this great country and clearly reflects the values expressed in the motto of West Point. Accordingly, the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy hereby presents the 2000 West Point Sylvanus Thayer Award to Dr. Henry A. Kissinger.

Speech

Remarks by Dr. Henry A. Kissinger upon receiving the Sylvanus Thayer Award

West Point – 13 September 2000

General Christman, Distinguished Guests, Members of the Corps:

I came to this country as a refugee from totalitarian oppression. When I was drafted into the United States Army, where I served for over three years before I was transferred to military intelligence, I served in the 84th Infantry Division. (And my brother, who was here as well, served in the 24th Infantry Division on Okinawa.) I always say that I landed on Omaha Beach, but I don’t tell people that it was six weeks after the contested landing. Later on I was transferred into the division headquarters, in fact, in the regimental intelligence, and so I have experience at least at the fringes of combat and a little bit of combat. I served there in the Battle of the Bulge, and the advance across Germany.

More important than that, the 84th Infantry Division was composed of soldiers from Wisconsin and Illinois. It was the Rail Splitter Division, and it was my introduction to the heart of America. I served for two years with these people, without whom I would never have understood what America really represents. So I owe much of what came later to the extraordinary opportunity I had of serving with an infantry division in World War II.

I must also say how much it means to me that my family can be here with me — my wife and my brother, my brother-in-law and their families, and so many of my friends who have sustained our lives. But I’d like to say a special word about two West Point graduates, for whenever people list achievements ascribed to me, their names should always be listed together with mine.

When I eventually went to Washington as National Security Advisor, we had 550,000 troops in Viet Nam. Some of those who had put them there had by then joined the peace movement. We had to extricate those troops with honor in an atmosphere of public demonstrations and civil disobedience, and with almost all of the media violently opposed to the war. I mention all of this because at that time I said, “I need a combat officer on my staff, somebody who has been to Viet Nam; somebody who can explain the meaning of the various recommendations that we may or may not receive because I have then to pass on to the President an analysis of what those recommendations imply.”

I had the good luck that someone recommended Al Haig, who has gone on to great things on his own. But he wasn’t even my deputy. He was a kind of military assistant at first, responsible for relations with the Pentagon, though he soon became my deputy, and we could not have gotten through that period without his fortitude, without his courage, and without his patriotism. Then he went off and became Vice Chief of Staff of the Army and, when Watergate descended upon us, he became Chief of Staff to President Nixon. Thereafter we had another period of the closest collaboration, which is now sometimes viciously misrepresented in books that have appeared. So I would say again, our country would not have gotten through the Watergate period if Al Haig had not been there to keep the ship of state steady and to help manage the crisis.

And then, when Al left me to do great services for the country as NATO commander and then as Secretary of State, I was unbelievably fortunate in getting to know another West Point graduate, Brent Scowcroft. Brent Scowcroft was at that point, military assistant to President Nixon. It was never fully clear to me what exactly a military assistant to the President does, except to carry the war plans around in case there is an emergency. He and I had the opportunity on presidential trips to have long conversations, which showed me that he was a man of extraordinary knowledge and truly sterling character and, shall I say, having the dedication which I believe is characteristic of the men and women in the Corps of Cadets. He became my deputy, then my successor, and went on to serve as security advisor in a subsequent administration.

After Watergate, we had to manage a transition of presidencies under truly tragic circumstances. Here was Gerald Ford at the helm, an un-elected president at the end of a Middle East War, at the beginning of our relationship with China, at the height of the Cold War, and meanwhile, the entire administration had to be reconstituted.

Again, Brent Scowcroft’s wisdom and loyalty and dedication have meant an enormous amount to our country, and have meant an enormous amount to me as his friend. I want to thank the United States Military Academy for the great national servants it has trained, men who have sustained me, from whom I have learned so much, and who have supplied a basic aspect of the structure of my life. I want to thank them both, together with my other friends here, for coming and sharing in this honor.

I have had the privilege of serving in the Army and then, as fate would have it, I was in Korea for six weeks during the Korean War in 1951. There, I visited the units and was at the front, north of Seoul. I also visited every corps area or military region in Vietnam before I became National Security Advisor, and then, of course, I visited it several times as Security Advisor. As a student of foreign policy, I have had many opportunities to reflect about the relationship of a nation’s power to its objectives.

We, as a country, have had a terrible time, not so much in winning our wars, but in ending our wars. Having always lived securely between two great oceans, with never a powerful neighbor, we have developed the idea that conflict is unusual. We tend to think that wars are caused by evil men or by some violation of some recognized international law, and we are embarrassed to affirm that our national interest is an objective. President Woodrow Wilson said, “we don’t want a rivalry of power, but a community of power.”

We won in Europe in World War II, but we could not convince ourselves that the location of the front lines at the end of the war would determine the political structure of Europe for a long time to come. And when Winston Churchill called attention to that reality, we claimed that we had overcome history, that history held no lessons for America because we were going to change all the previous patterns. In World War I, we fought a war for self-determination and to make the world safe for democracy, but we wound up with a Europe that was structurally more vulnerable than the one that had begun the war; and, actually, Germany was better off strategically as a result of World War I than it had been. Before the war it had had powerful neighbors. As a result of our ideas of the peace, it became surrounded by weak neighbors, and it was only a question of time until Germany threw off the shackles of disarmament that had been imposed upon it — after which it was strategically stronger than before.

And this pattern can be traced through all our subsequent enterprises. In the Korean War we had similar difficulty defining our objective. We began by wanting to repel aggression. Then, when we achieved victory, we decided to unify Korea; and then, when the Chinese intervened, we retreated to stalemate. But I think it ought to be a fundamental principle of American national strategy that countries that tackle us militarily must be worse off as a result of their aggression than they were before. Therefore, I believe that whatever mistakes may have been made in the aftermath of the Inchon landing, once China entered the war, MacArthur’s basic judgment was correct. I remember when I visited Korea in 1951, that all our military leaders on the ground were quite convinced that if they could pursue the offensive they could have achieved a success. Instead, we stopped military operations when the negotiations started and as a result found ourselves in a stalemate.

Now what does one mean by success? How far should the offensive have been pushed? Many of you know that I am a strong advocate today of cooperative relations with China, but not when we are in the middle of a war with it.

And now I want to say a few words about Vietnam. At the reception, a number of you graduates were kind enough to come up to me and make some friendly remarks about my role or my contribution to bringing about an end to the Vietnam War. I do not look back to the Vietnam period with great satisfaction. We extricated our forces without a debacle, but that is not a war aim that is worthy of America. The administration in which I served inherited a large American commitment in Vietnam. We did not place the forces there, but I believe that those Presidents who did place the forces there, did so for reasons of which we have every cause to be proud. They wanted to prevent the spread of communism at a formative period in Asia. They were dedicated to building democratic institutions in a new country. They were too American to understand that you could not do all these things simultaneously, that, in the middle of a guerilla war, you cannot implement all the maxims of the American constitutional system, and that you get no awards for losing with moderation. I believe that as calm returns to reflection, the time will come when we will remember that the people who were on the moral side of that issue were those who maintained that we should not sacrifice tens of millions of people who, in reliance on the American word, had thrown in their lot with us; and that we had an obligation to previous administrations, whose political views we did not share in other ways, to assert a continuity of American policy.

So we did the best we could, but I’m not happy with the outcome. And we must never permit a situation like this to arise again, or enter a conflict whose successful end we cannot describe. We have had this problem in almost every administration. In the Gulf, we performed a great service in preventing the success of the Iraqi aggression, but when we had cleared Kuwait, we began to lose focus on the purpose of the exercise and had difficulty once again in defining what we should be attempting to achieve. I believe that it would have been better not to go to Baghdad, but to destroy as many Iraqi Republican Guard divisions as we could, until they either overthrew Saddam or were forced to seek a political outcome that demonstrated that, when you fight America, you cannot end with the status quo. I give great credit to the people who organized the Gulf War, who built an alliance, and who won it; and I mention it primarily because, whenever we confront a crisis, we are better at defining the moral cause than at giving it a political expression.

One thing that is happening in our present period is that our country is going through an overlap of three generations. There is the generation, for which I speak, that remembers what we stood for at the end of World War II, and for some decades after. We believe in the importance of American power, and we are not ashamed of the role America performed in creating a new international system. But then, there is a generation whose formative experience took place during the Viet Nam War. They were not in the military regions of Vietnam, but in the protest movement. And they have always felt embarrassed about American power, preferring universal values which they would like to apply all over the world, provided only that they involve no casualties. That generation stresses the so-called soft issues, and they have wound up now with world-wide commitments but no willingness to carry them out.

Now they are followed by yet another generation. I was at an Ivy League school the other day. And the faculty was having a great old time harassing me about Vietnam, which bored the students absolutely to tears—and by the way, I also had the impression that not all the students knew whether the Vietnam conflict had been before or after the Spanish-American War. But this next generation, brought up on the computer, is one that considers service on Wall Street more important than service in the government. It has at its disposal an extraordinary range of knowledge unheard of in any previous period, but that knowledge is not always coupled with understanding and perspective. The great things in history have occurred because leaders bridged the gap between what people had experienced and the vision of which they were capable.

At the moment we are oscillating in between these various generations. When I look at Kosovo, I see that we had a good cause there, but we don’t know how to end it. I had been opposed to the war because I thought we had few national interests there. But I supported it strongly once we were in it, because defeat would have weakened NATO. Now I feel that, if we stay there indefinitely, we will become the targets of the liberation movements in whose name we fought the war to begin with. But if we leave, there will be a blow-up in all the surrounding countries, and it is a dilemma which we have created for ourselves.

But the major point that I want to leave with you as you go out from here and are someday leading young men and women into danger is this: it will depend on your courage and inspiration whether the traditions and the service that has epitomized our country’s international role will continue. A favorite academic debate, and a favorite intellectual debate, is the argument between idealists and realists. The idealists are supposed to be noble and inspirational while the realists are supposed to be trudging around in the muck, thinking of the immediate practical solutions. But ideals for which you are not willing to sacrifice are just rhetoric, and when you advocate military engagements for which you are not willing to sacrifice, you are just pursuing the fads of the moment. We are in danger of drifting into this position. You, of the Corps of Cadets, by the mere fact of being here, testify to a sense of our values because if you wanted an easy life, you would be at other universities; and if you simply wanted a career, you would be on Wall Street. You know what your country is going to ask of you. You know that the world has never been more complex.

The people with the great ideas claim that there is one universal recipe which, if you pronounce it often enough, will implement itself without any effort on our side. But in the real world, where we live, we see parts of the world that have democratic traditions and other parts of the world, like Asia, which are practicing the balance of power. And you have yet other parts of the world, like the Middle East, which are more similar to the era of the religious wars of the 16th century than to our period. And there are other parts of the world, which you can’t even begin to compare, that are at the very beginning of formation. In all of these, in one form or another, we on the political side will have to decide what constitutes a vital American interest. And we mustn’t be ashamed to have an interest. Our interests should be broad, they should be elevated, they should be democratic, but they should also be feasible. And none of these objectives has any meaning but for men and women like you of the Corps of Cadets who have dedicated your lives to service.

One of the most moving addresses I have ever read is the one of General MacArthur when he was here in 1962. It is because that spirit continues. There was a Roman saying that went like this: “The republic has been great because of its virtues and because of its heroes.” That was true then, that is true now, and that is why I thank you for the honor of speaking to you tonight.

Thank you.