By Ian Winer ’96, Guest Author

“Yes.”

“No.”

“I do not understand.”

“No excuse.”

Throughout the entirety of my first year at West Point, these were the only four acceptable answers to any question. I collided with this new reality a generation ago, on Reception Day in June 1992. A cadet wearing a red sash told me to learn only these four responses during Beast Barracks. He did not mention that these same four answers would also define and eventually rescue me over the course of my journey for the next three decades, one that took me through addiction and alcoholism into sobriety. “Yes,” “No,” and “I do not understand” described my existence for many years, but the fourth response, “No excuse,” saved my life. A medical discharge after graduation, a loss of purpose, and a life of excess led to a downward spiral of substance abuse and misery that I did not understand. After a final surrender to my emptiness 11 years ago, I chose to get sober and live a life of service, with plenty of setbacks but without excuses.

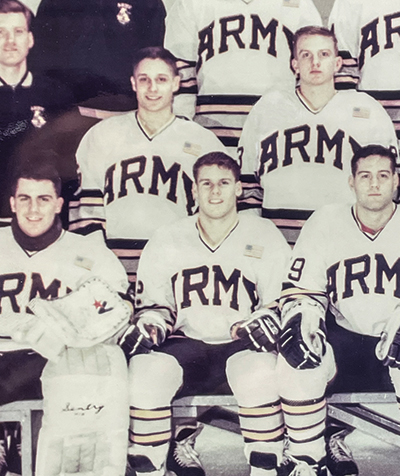

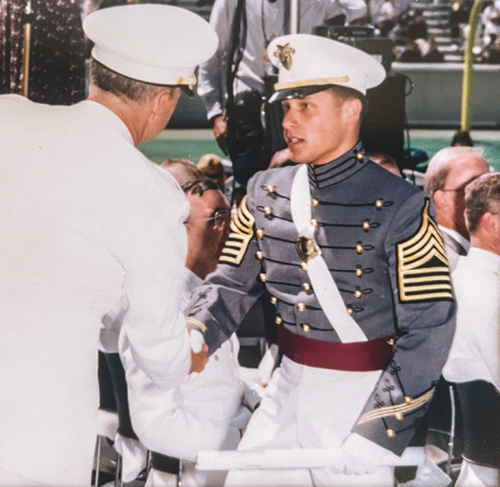

During his 1962 “Duty, Honor, Country” speech, General MacArthur told the Corps of Cadets: “…in war there is no substitute for victory,” and, before a bout with pugil sticks at Camp Buckner, I learned: “There are two types of fighters: the quick and the dead.” My life at West Point was a series of measurable goals, with success and failure most often defined by binary “yes” or “no” outcomes. Corps squad ice hockey, Wreath Award, Airborne, Air Assault: Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Hundreds of hours on the Area, drinking at the Firstie Club every available chance, the annual spring break in Cancun: Yes. Yes. Yes. No matter how healthy or how risky, the answer had to be “yes” because there was no replacement for victory in war and I approached every aspect of life as a battle. Then, one day in March 1996, when I needed just one more “yes” to put a final exclamation point on my cadet experience, I was told, “No.” I failed the commissioning physical. The medical board told me that I would be allowed to graduate, but there would be no “real Army” in my future. Ever. The clarity of my first two responses at West Point was soon replaced, in civilian life, by my third response of “I do not understand” and the uncertainty surrounding it.

I was devastated over my inability to commission, but I was not going to grieve my loss. Grief was for the weak. Instead, I did my best to determine what a fighter does without a fight. I quickly found the most high-energy environment that required the least amount of emotion: Wall Street. “Duty, Honor, Country” became “Money, Never, Sleeps.” At USMA, the epaulettes showed rank. In the world of finance, it was a house, a car, or even a pair of cufflinks that separated echelons. As the years went on, I increased my rank on Wall Street. From the outside looking in, I was a success. But I was miserable. For the first time in my life, I did not understand. That third response came to define my daily struggles. The only respite for me from the pain and emptiness was to drink or do drugs. These substances eased my suffering for some time, until they evolved into full-blown addictions. I lost any zest for life and resigned myself to believing I would never find a purpose. I did not understand why anything mattered, other than the next high.

“I began to understand the possibilities of a life without drugs or alcohol. It was at this moment that my fourth response of “No excuse” became my mantra and saving grace.”

— Ian Winer ’96

Then, a miracle happened. On March 23, 2013, I did something that was incomprehensible and totally unacceptable during most of my life and especially while at West Point. I surrendered. The disease of addiction had beaten me senseless. I raised the white flag. It took decades of pain and illusions of control before I finally admitted I was completely powerless. On that day in March, more than 11 years ago, I decided that I needed directions to a better life and took a leap of faith believing that sobriety could be that avenue for my salvation. I asked total strangers for help. There was nothing to take charge of anymore because I was no longer in charge. As each day passed, the fog lifted, and I began to understand the possibilities of a life without drugs or alcohol. It was at this moment that my fourth response of “No excuse” became my mantra and saving grace. The rub with sobriety is that I now feel emotions again, both good and bad. In many ways, life has been more difficult during my recovery. I now have nothing to use as an excuse for my behavior. Life is hard when one does not make excuses. “No excuse” got me farther in business than anything else I learned over my decades on Wall Street. Whenever I made a mistake, my explanation of “no excuse” caused my bosses’ heads to spin around. They had never heard that before. Most people on Wall Street would blame anyone but themselves for mistakes. While I allowed no room for excuses in business for decades, I had an endless number of excuses over the same timespan for why I was a poor brother, friend, and husband. This is the cruel beauty of sobriety. I show up in life now for those who need me. I still make plenty of mistakes, but I do not make excuses for any poor behavior, and I make amends to people I harm. To err is human, but to own that error and not make any excuses is my daily work. The fourth response gives me purpose.

The rub with sobriety is that I now feel emotions again, both good and bad. In many ways, life has been more difficult during my recovery. I now have nothing to use as an excuse for my behavior. Life is hard when one does not make excuses. “No excuse” got me farther in business than anything else I learned over my decades on Wall Street. Whenever I made a mistake, my explanation of “no excuse” caused my bosses’ heads to spin around. They had never heard that before. Most people on Wall Street would blame anyone but themselves for mistakes. While I allowed no room for excuses in business for decades, I had an endless number of excuses over the same timespan for why I was a poor brother, friend, and husband. This is the cruel beauty of sobriety. I show up in life now for those who need me. I still make plenty of mistakes, but I do not make excuses for any poor behavior, and I make amends to people I harm. To err is human, but to own that error and not make any excuses is my daily work. The fourth response gives me purpose.

In 1992, at the United States Military Academy, a young new cadet from New Jersey marched across a large plain of freshly cut summer grass to the great joy of hundreds of parents, including his own. In his head, he heard those four responses: Yes; No; I do not understand; No excuse. It was time to join the service. I was that cadet.

In 2024, in Los Angeles, a man reflects on a journey from addiction to sobriety clearly defined by those same four responses. He does his best to be a good man. He has made a lot of progress but is far from perfection. It is now time to be of service, which for me takes different forms: working in private equity and investing in defense technology companies, assisting military members who are transitioning to civilian life, and, above all else, helping members of the Long Gray Line who struggle with addiction and alcoholism. I aim to continue this service for the rest of my days.

Ian Winer graduated from West Point in 1996 with a degree in International Relations. He works in private equity and focuses on investing in companies pursuing new defense technologies. He is the author of Ubiquitous Relativity: My Truth is not The Truth and lives in Los Angeles with his wife and their labrador, Ulysses.

Hear more from Ian Winer ’96 on the WPAOG Podcast.

Read the complete Summer 2024 edition of West Point magazine here.

What do you think? Click here to answer four questions.