By Keith J. Hamel, WPAOG staff

Cadets are now preparing for a peer adversary in their final Cadet Summer Training graduation requirement.

In 2020, COVID-19 impacted the operating procedures at West Point in various ways. One of these was the cancellation of Cadet Leader Development Training (CLDT), the pinnacle of Cadet Summer Training, which is designed for rising firsties and those members of the rising cow class who will be in key summer leader positions the following year. The COVID pause allowed Colonel Alan Boyer ’96, the Director of the Department of Military Instruction (DMI) at the United States Military Academy at that time, an opportunity to revamp CLDT. Gone was the focus on counter-insurgency training that had dominated CLDT for more than a decade, replaced by peer-to-peer fighting in a multi-domain environment in anticipation of a conflict in the Far East.

“The Chief of Staff of the Army raised the Pacific threat, and USMA jumped on it, making the DATE [Decisive Action Training Environment] Pacific operational environment part of MS300 [Platoon Operations] and CLDT,” says Lieutenant Colonel Dan Stuewe, then Chief of Military Science and Training. DATE Pacific provides the U.S. Army training community with a detailed description of the conditions of multiple composite operational environments in the Pacific region, giving trainers a tool to assist in the construction of scenarios for specific training events. “Through a liaison with the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command’s G2, the intelligence center that owns the U.S. Army’s training scenarios, DMI received guidance and resources that puts CLDT a little ahead of the game versus regular army units when it comes to DATE Pacific,” says Stuewe. One such resource is the use of vismods (vehicles with visual modifications) on the CLDT training lanes to act as opposing forces’ assets.

“CLDT shows cadets that they have the knowledge and demands that they go lead. Having completed CLDT, I am more confident in myself and my peers; when we go back to the Corps, we’re ready to show the underclass cadets that what they’re learning is one part of a much larger picture.”

—CDT Matt Williams ’24, 1st Platoon, Bravo Company

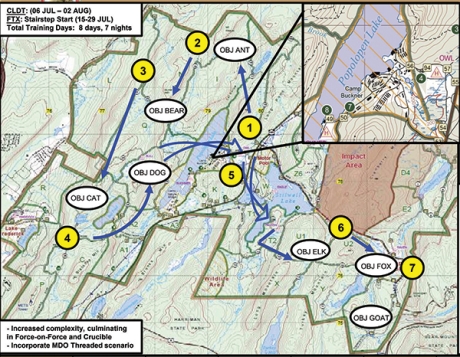

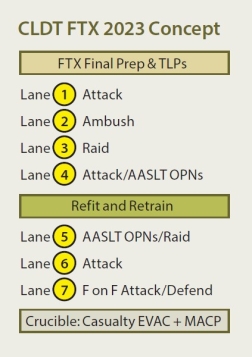

Not only has the content of CLDT changed after 2020, but the form has changed as well. “CLDT used to be a shotgun blast start with six companies rotating through three, 96-hour training lanes—offensive, defensive, and movement-to-contact—all at the same time,” says Major Franklin Banegas, CLDT Chief of Staff. “Now DMI employs an eight-lane waterfall model.” Not only does this model use a three-phase, 21-day iteration system—Warrior Week, Field Training Exercises (FTX), and Recovery—it uses a staggered design so that only the four platoons of one of eight training companies are performing a particular training task per lane on a given day. For example, according to the 2023 CLDT calendar, on Day 9 Alpha Company was on Lane 2 of the eight-day FTX, Bravo Company was on Lane 1, and the remaining companies were still performing the FTX prep tasks of their five-day Warrior Week (e.g. combatives training, cold load training, SOPs and field craft refinement, platoon trainer-led instruction, etc.). “Using a waterfall model allows DMI to create complexity as CLDT unfolds,” said Banegas. “The FTX lanes get progressively tactically harder, and the field problems and scenarios get more elaborate, with more dilemmas given to cadet leadership.”

The scenario for the FTX, which acts as an entire narrative running throughout the training, begins the night before Lane 1: The company receives a mission for a company attack on an objective, for which the platoon is the decisive operation. On Lane 1, in a pre-determined order, each platoon of a company conducts an attack that leads to intel of an enemy resupply or movement of a key weapon system, prompting the platoon to plan an ambush for the following day. On Lane 2, each platoon conducts an ambush and receives additional intel, leading to a raid the following day. On Lane 3, each platoon conducts a raid on a high-value, air defense artillery (ADA) asset in order to enable air operations into the area of operation (AO). “The mission of the FTX from the get-go is to enable air operations, and ADA is a threat to this objective,” says Banegas. “We need to get the cadets to stop thinking myopically and start thinking more broadly, seeing that operations are not completed in isolation but are done in combination with higher HQ.” During Lane 4, each platoon receives an order to take over an airfield so that it can exfil out. This leads to an attack on a landing zone, after which each platoon is air assaulted back to Camp Buckner for a 24-hour refit. “By this point in the FTX, platoon SOPs are more set, cadets are starting to understand the overall mission and their role in it, and they are becoming more familiar with how their teammates move and communicate,” notes Banegas.

“The lane walkers [platoon trainers] would give us nuggets of info so that we could start to think about what was going on outside of our individual platoon mission. It helped me realize that we were not operating as just a platoon but as part of a larger company and battalion mission.”

—CDT Mackenzie West ’24, 4th Platoon, Foxtrot Company

The scenario continues during the refit. At some point during its 24-hour respite, the platoon receives word that it is to air assault into a new AO and conduct a raid on urbanized terrain during Lane 5. Right after the raid, the platoon receives a fragmentary order to recover a downed friendly aircraft before the enemy can reach it. On Lane 6, the platoon conducts an attack on one of the enemy’s last strongholds in the AO, while Lane 7 is a force-on-force exercise, with one platoon on offense and another on defense. The final event of the FTX is the Crucible, a 3-mile movement during which cadets negotiate various physically demanding stations, culminating in carrying a casualty a mile to the Combatives Pit, where the cadets engage each other in combative training. This grueling event is meant to push the cadets mentally and physically while building cohesion through shared hardship.

While the enemy and mission structure of CLDT has changed since COVID, the overall objective of CLDT has not. Often described as mini-Ranger School, it’s still about tactical problem-solving and individual technical proficiency under great amounts of physical and mental stress. “The traditional stressors of CLDT are still present,” says Banegas: little sleep, little food, heat and rain, peer dynamics, and rucking 50-60 pounds across the West Point training reservation’s rocky and rugged terrain (platoons end up traveling more than 50 kilometers during the eight-day FTX).

Not only that, DMI constantly adds unexpected elements into the scenario: indirect fire typical of a peer enemy, 120 mm mortars, casualty evacuations, medical evacuations, and more. “What are you going to do now, platoon?” is a common refrain heard from trainers on the lane. “This is not walking through the woods and shooting a weapon,” says Lieutenant Colonel Adam Sawyer ’00, the current DMI Director. “It’s extremely intellectual, with the tough, realistic scenarios teaching cadets the application of military art and science as they apply to Army methodologies so they can develop a tactical plan that will defeat their enemy.”

“Making tactical decisions under duress is the biggest upside of CLDT,” says Banegas. “Most cadets are not going to branch Armor or Infantry, but we still need to create warriors out of medics and Ordnance officers.” Graduates of CLDT will demonstrate confidence and proficiency in leadership attributes by applying the Army’s Operation Process in the preparation and execution of missions preparing all of them for the rank of second lieutenant upon commissioning.

Training and Grading

CLDT instructs, trains, mentors, and assesses First Class and selected Second Class cadets on basic warrior and leadership skills.

“Both Cadet Basic Training and Cadet Field Training put you in a position to perform a task, and they grade you on how well you can perform that task. CLDT, on the other hand, is not an objective score, as there is more than one way to complete a mission on the lanes; instead, it’s based on how much your peers trust you, your confidence level, and your ability to make quick decisions.”

—CDT Jacqueline Reagan ’24, 3rd Platoon, Bravo Company

Each platoon is assigned two USMA platoon mentors, officers assigned to the USMA academic program, and one task force platoon mentor, a non-commissioned officer who is a subject matter expert in tactics. In 2023, the task force came from 1st Battalion, 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division. The two USMA mentors provide leadership and mentorship to cadets in their platoon during CLDT and complete a leadership evaluation on every cadet in the platoon via the LARA app at the end of CLDT. “We use the app to add notes, submit pictures, and tag leadership attributes for the cadets,” says Major Logan Lee ’12, an Instructor in the Department Geography and Environmental Engineering who served as a platoon mentor for 3rd Platoon, Foxtrot Company. Each lane of the FTX also consists of three officers and three non-commissioned officers from the task force. They serve as platoon trainers and provide the tactical evaluations of cadets through the SPARTA app. Finally, each lane has three additional non-commissioned officers who act as squad leader trainers and assist the platoon trainer grading team in the assessment of squad leader tactics during that lane.

During the FTX, each cadet in a platoon is evaluated twice: once as they are being tasked as the platoon leader (PL) or platoon sergeant (PSG); once as a squad leader (SL) in the platoon (platoon mentors determine the cadet leadership rotation matrix to ensure that all cadets in the platoon receive the proper number of field and garrison evaluations). The PL/PSG evaluation is worth 30 percent of a cadet’s overall CLDT grade, and the SL evaluation is worth 20 percent (both tactical performance assessments). The platoon trainer grades cadets on how well they apply troop leading procedures to planning a tactical operation, communicate a tactical order verbally and visually, and demonstrate an understanding of Army doctrine and small unit tactics in a field training environment. The remaining 50 percent of a cadet’s CLDT grade comes from the platoon mentor evaluation, along with cadet peer evaluations (both assessing leader attributes and competency). The platoon mentor grades cadets on their character, presence, intellect, trustworthiness, communication skills, and ultimate execution of tasks.

Cadets need to pass one of two leadership evaluations and score better than 67.9 percent on graded events to graduate from CLDT. Those who do prove that they have the aptitude required to competently and confidently lead soldiers in complex environments upon commissioning.

Read the complete Fall 2023 edition of West Point magazine here.