By Keith J. Hamel, WPAOG staff

The U.S. Military Academy has always developed leaders for the Army and the nation, but the way in which it has conducted this mission has evolved over time, changing several times in the last hundred or so years.

The Fourth Class (Plebe) System

For the longest time, going all the way back to the Thayer era of the Academy (1817-33), West Point had molded cadets using the Fourth Class System. Sometimes referred to as the Plebe System and based upon traditions and customs, this method of leader development had new cadets learning their role in the Corps from upperclass cadets. Prior to its official sanctioning in 1919, the Fourth Class System required plebes to perform certain duties, many of which were of a personal servitude nature (carry water, make beds, clean equipment). The Fourth Class system also put restrictions on plebes, making their new environment an obstacle to overcome. Some upperclass cadets took advantage of the system and occasionally harassed plebes, believing they were doing so for the benefit of the Academy and the Corps. The thinking was that those who could take the pressures of the Fourth Class System would make a worthy cadet and future officer. As such the Fourth Class System was seen as an attritional model, “weeding out the weak.”

When Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, Class of 1903, became Superintendent in 1919, he appointed a committee of cadets to codify the customs and traditions that should be handed down from class to class through the Fourth Class System. His codification was also designed to end practices that were receiving negative scrutiny from a public unfamiliar with the traditions of the Academy. As sanctioned by MacArthur, the Fourth Class System dictated when plebes were to report to formation, what duties they were to perform in the Mess Hall, how they were supposed to carry themselves at certain times,what knowledge they needed to retain, and what menial tasks they were required to do for their company (i.e., mail carrier, minute caller, laundry, etc.).

The sanctioned Fourth Class System underwent numerous reviews after 1919 (1941, 1946, 1962, 1969, 1979). With the 1969 report, certain activities—such as bracing, shouting at plebes, and the memorization of copious amounts of plebe knowledge—were supposed to be eliminated; however, opponents within the Academy resisted any changes to the long-standing traditions of the Fourth Class System. Still, according to Lori Stokan’s (Class of 1986) report “The Fourth Class System: 192 Years of Tradition Unhampered by Progress from Within,” at the start of the 1980s more emphasis within the system was being placed on creating a more realistic senior-subordinate relationship between upperclassmen and plebes and on positive leadership, and the results of the 1986 First Class Questionnaire indicated an 88 percent approval of the updated system. Despite general approval of the Fourth Class System as a “rite of passage,” a 1988 USMA Inspector General report found very little leadership development value in the system for upperclass cadets, and a 1989 Institutional Self Study recommended that the Commandant review the impact of the Fourth Class System.

Cadet Leader Development System (CLDS)

In 1989-90, Lieutenant General Dave Palmer ’56, the Superintendent at the time, directed a full review of the Fourth Class System, appointing three committees—one consisting of cadets, another of faculty and staff, and a third of alumni—to recommend improvements. The result was a new, developmental model of leadership called the Cadet Leader Development System, or CLDS. Intended to be “evolutionary, not revolutionary,” CLDS retained some of the elements of the traditional plebe experience, yet it also set progressively higher levels of expectations on the cadets of the Third, Second and First classes. Focusing on the “Be” component of the Army’s “Be-Know-Do” model for leadership, CLDS was primarily about what it means to be a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army.

“CLDS will significantly enhance our ability to inculcate within cadets of all four classes those values, ideals, and principles that are integral to the exercise of effective leadership,” wrote Brigadier General David Bramlett ’64, the Commandant of Cadets, in the January 1991 issue of ASSEMBLY. He returned to this topic in the September 1991 issue, saying, “Each year the development process actually intensifies in a different way, as each cadet assumes a leadership role both in a specific position and by being a member of a particular class.”

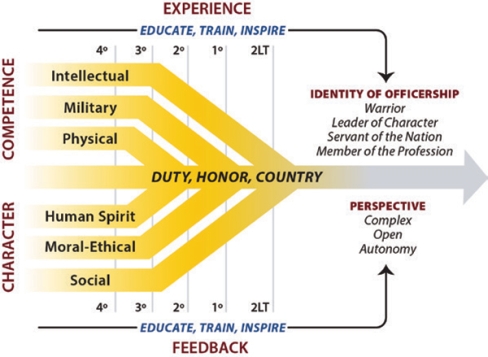

With CLDS, West Point progressed from a “Fourth Class System” to a “Four Class System,” establishing a roadmap for leader development throughout the entire four-year experience focusing on posture/bearing, cadet mess policies, knowledge, discipline, duties, restrictions, and customs/courtesies. CLDS coordinated and integrated cadet developmental activities across the entire West Point experience by essentially funneling the competencies (intellectual, military, physical) and character traits (human spirit, moral-ethical, social) needed for officership through progressively narrower targets from a cadet’s Fourth Class year to his or her First Class year so that each cadet, upon commissioning, identifies as a warrior, leader of character, servant of the nation, and member of the Profession of Arms (see graphic on page 42). Writing in 2012, Brigadier General Lance Betros ’77 (Retired), said, “CLDS represented the most coherent and progressive system of overall leader development ever established at West Point.”

West Point Leader Development System

Interestingly, just as Betros was making his pronouncement, the Academy was introducing its third major change to the way it conducts its leadership development mission. Called the West Point Leader Development System, or WPLDS, this model is the integration of individual leader development across USMA’s four pillar programs (academic, military, physical, character) with leader development opportunities throughout the West Point 47-month experience in a culture of character growth. WPLDS is both influenced by Army doctrine and based on research of individual and organizational development (e.g., Kegan’s stages of adult development, relational development systems theory, and more).

Building off CLDS, WPLDS sets high standards, allows cadets to learn from failure, and makes cadet leader development a community-wide initiative (establishing a role for all USMA staff and faculty). As originally defined, WPLDS had eight outcomes for West Point graduates: 1) live honorably and build trust; 2) demonstrate intellectual, military, and physical competence; 3) develop, lead, and inspire; 4) think critically and creatively; 5) make sound and timely decisions; 6) communicate and interact effectively; 7) seek balance, be resilient, and demonstrate a strong and winning spirit; and 8) pursue excellence and continue to grow. When WPLDS was re-evaluated in 2017-18, these outcomes were revised to three simple directives: live honorably, lead honorably, and demonstrate excellence.

Today, an Academy Character Program, led by the Simon Center for the Professional Military Ethic, supports WPLDS and helps cadets understand what it means to be a commissioned leader of character who lives and leads honorably by educating them on the professional standards, organizational values and personal virtues that comprise “honor” in the Army profession. According to the USMA Goldbook, which details the tenets of USMA’s character pillar, in supporting WPLDS, “the Character Program operates along three deliberate, progressive, and mutually reinforcing lines of effort: 1) Stewardship of the Cadet Honor Code, 2) the Cadet Character Education Program (placing specific emphasis on the Army value of Respect, especially as it relates to eliminating attitudes and behaviors that contribute to trust-shattering misconduct such as sexual harassment, sexual assault, and unjust discrimination), and 3) the Superintendent’s capstone course, MX400: Officership.” Finally, WPLDS adds to Army doctrine by integrating into its framework five facets of character—moral, civic, performance, social, and leadership— which help operationalize character into observable behaviors and provide a way to gauge character development.

“Developing West Point graduates for an uncertain and complex future is a daunting but achievable goal,” notes Developing Leaders of Character, the Academy document that codifies WPLDS. “WPLDS develops leaders who will thrive in complex, decentralized operating environments, maintain the high standards of the Army profession, and meet the expectations of the nation they serve as trusted Army professionals.”

“CLDS coordinated and integrated cadet developmental activities across the entire West Point experience by essentially funneling the competencies (intellectual, military, physical) and character traits (human spirit, moral-ethical, social) needed for officership through progressively narrower targets from a cadet’s Fourth Class year to his or her First Class year so that each cadet, upon commissioning, identifies as a warrior, leader of character, servant of the nation, and member of the Profession of Arms.”

Read the complete Spring 2023 edition of West Point magazine here.